In

the annals of American espionage, Jim Nicholson, pictured above with his son Nathan in the U.S. Army uniform, holds four superlatives.

He’s the

highest-ranking CIA officer convicted of selling America’s secrets to a foreign

nation. He’s the only US intelligence officer convicted twice of betraying his

country. And he’s the only one to have pulled it off from behind prison bars.

But Nicholson’s

fourth dishonorable distinction offers the most drama: He’s the only CIA

officer ever nabbed in a literal spy-versus-spy operation inside the agency’s

headquarters at Langley, Virginia. He was targeted by a brother officer in a

daring undercover investigation.

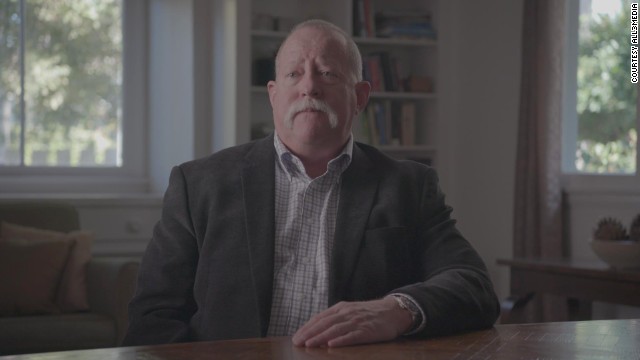

John Maguire, pictured above,

became the ultimate "inside man" in a case that shows how far

counterespionage investigators will go to catch a mole in their midst. The

story of Maguire's top-secret operation, told for the first time in the book "The Spy's Son",

provides a rare portal into the persistent spy wars between Moscow and

Washington.

Maguire's

assignment came during a rough patch in his career. He had been "sent

home" -- agency lingo for being taken out of the field — after getting

crossways with his boss. Maguire was exiled to the worst imaginable position

for a highly skilled case officer: a desk job in human resources. But in 1996,

he was given a chance to redeem himself as part of a joint CIA-FBI

counterespionage operation.

That’s where

Maguire comes in.

Bryan Denson

is an investigative journalist in Portland, Oregon. He’s the author of The Spy’s Son: The True Story of the Highest-Ranking

CIA Officer Ever Convicted of Espionage and the Son He Trained to Spy for

Russia (Grove Atlantic, 2015).

John

Maguire sat in a cubicle village on the second floor of CIA headquarters, a

clean, well-carpeted place full of file cabinets and misery. After fourteen

years of exciting spy work, he now labored in utter obscurity in a pool of

human resources mopes. Maguire

had spent most of his years in the agency on the front lines of the Cold War,

although more recently he labored as a counterterrorism operative in the Middle

East. He had served in such garden spots as El Salvador, Honduras,

Lebanon, and Iraq. But now it was abundantly clear that at forty-two, his

once-promising career in espionage was over.

Maguire

had gotten crossways with his boss, the Near East Division chief, for refusing

to take an overseas posting in Karachi, Pakistan. His penance was a position in

HR, in the bowels of the CIA’s Original Headquarters Building, part of the

agency’s sprawling, highly secured compound in the Langley community of McLean,

Virginia. There he drank sweetened coffee and pushed pencils amid the agency’s

plebes, poring through the personnel files of other CIA officers to determine

those worthy of promotions. He found it disheartening to labor through the

applications of agency employees who, unlike himself, might actually be

promoted.

Maguire’s ennui

was broken, from time to time, by the prank calls of colleagues still

performing actual spy work. Some disguised their voices to ask about their

promotions packets before busting a gut. Others phoned to make such helpful

declarations as, “You’re so f***ed.” One day, in the spring of 1996, Maguire’s

phone rang and he heard the voice of Anna, the secretary of the Near East Division.

Anna was a powerful figure in the

division, something of an aging Miss Moneypenny, and as part of the senior

secretarial pool, she enjoyed the oblique horsepower of her division chief.

When Anna called, you paid attention. When you needed help, she was your

oracle. Need to proof-check an official memo? She pored over it, caught your

errors. Need to reach an overseas leader, a business figure, someone at the

White House? She had the number. Screw up badly? She dressed you down, leaving

you standing with your shoes smoking as if you’d been struck by lightning. Anna

was a striking, statuesque woman with raven hair. All the senior secretaries in

the CIA had juice. If they liked you, they could make your life easier. Anna

seemed to like Maguire. Anna seemed to like Maguire.

“How are you doing?” she asked.

I’m

trying not to kill myself in my seat,” he said.

“Come upstairs,”

he heard her say. “Don’t tell anybody where you’re going. Just leave your desk

and come up here to me right now.”

“OK.”

Like so many times

in his career, Maguire could only imagine the fresh patch of hell in front of

him. He had served seven years as a cop in his native Baltimore, then fourteen

more as a spy. He understood the swift, decisive nature of upper-management

bureaucrats, whose sudden decrees often fell into subordinates’ laps like hot

coals. Maguire hauled his six-foot-three, 195-pound frame out of his chair and

slipped away quietly. He caught an elevator to the sixth floor, one level below

the penthouse of power, where the Director of Central Intelligence runs the

show. There, outside his boss’s door, he found Anna at her desk. She steered

him into the office, and the door closed.

He stood in front

of a familiar wooden desk, behind which sat Steve Richter, whom he had never seen without a

suit and tie. Richter, a

key part of the Directorate of Operations, the CIA’s clandestine wing,

oversaw spy operations across the Middle East. Maguire thought his boss was one

of the smartest and most talented of the agency’s senior intelligence officers,

and also one of the most vindictive.

The

previous fall, Richter had flown to London to tell Maguire of his next

assignment: Karachi. The move would have taken Maguire out of his work in

northern Iraq, and he wanted none of it. He had run spy and paramilitary

operations in the Middle East nation for five years, having first dropped into

Iraq for the Persian Gulf War. Maguire felt invested in Iraq’s future. It had

taken years to wrap his head around the country’s complicated, tribally based

culture, its Ba’ath Party leadership, and the wickedness of Saddam Hussein and

his power-sick sons, Uday and Qusay. He had hoped that his good work would be

rewarded with a promotion to a leadership post in Amman or Abu Dhabi.

Maguire

asked Richter to let him stay on in London. He was happy there, enjoying what

is known in Foreign Service parlance as an “accompanied tour” with his wife and

two daughters. Maguire told Richter he hoped to continue his vital work in

Iraq, where he had developed locals -- sometimes with trunks of cash -- to gain

secrets from inside Iraq’s seats of power.

Richter hadn’t

flown to London to negotiate. He urged Maguire to take the assignment and

report to the CIA station in Karachi. That’s when Maguire played his last card.

He told Richter that his wife, a registered nurse, had long told him there were

only two countries on the planet so full of filth and disease that she refused

to raise their girls in them: India and Pakistan. For those reasons, Maguire

told his boss, he would have to politely decline the job in Karachi. Richter

wasn’t accustomed to being told no. He left Maguire in stony silence.

Soon after,

Maguire got the cable letting him know he was being called back to Langley to

work in human resources, his requests for posts in the Middle East denied.

Now

he found himself standing in front of Richter’s desk

Maguire’s

boss, not known for warm and fuzzy moments with subordinates, didn’t invite him

to take a seat. It would be a short meeting. “I have an assignment for you,”

Richter said. “I can’t tell you anything about it.” He told Maguire that he

needed an answer then and there, and that a yes would be good for his career.

If he said no, all he had to do was go back downstairs and never utter a word

about the conversation. “You have to give me an answer now,” Richter said.

Maguire, flummoxed, glanced to his right. A stranger sat on the couch. The man

wore a nice suit and a blue badge denoting him as a CIA staffer. Maguire

figured he was a senior agency man. He planted his eyes on Richter’s face to

read his reaction to his next words.

“Can I ask a

question or two?”

Richter peered at

Maguire sourly. “You can ask,” he said.

Maguire turned to

the man on the couch.

“Who’s this guy?”

“I’m Ed Curran,” the stranger said. “I’m the

highest-ranking FBI agent assigned inside the CIA.”

F**k me, Maguire

thought.

His

mind flew back to Iraq and the troubles there. The FBI was still investigating

the CIA’s role in organizing an unsuccessful coup that March against Saddam

Hussein by his own military. Maguire and his team had rotated into northern

Iraq during that covert action (code-named DBACHILLES), which failed. Saddam

executed at least eighty of his officers involved in the attempted overthrow.

Maguire

feared that the new “assignment” Richter was offering might be a ham-handed

setup for questioning by the FBI. The appearance of Curran only deepened his

anxiety. Maguire’s choices seemed clear. He could turn down a potentially choice assignment,

whatever it was, and retreat to the cubicle dungeon and the slow immolation of

his soul. Or he could do as the paratroopers say in that instant before leaping

out of airplanes: Pull the cord, trust the Lord.

“F**k it,” he

said. “I’ll take it. Whatever it is, I’ll do it.”

“Wise choice,”

Richter said.

Maguire could

sense by the tone of his boss’s voice that the meeting was over. Curran, no

doubt amused by the exchange, gave Maguire orders: Go downstairs to the lobby.

Do not talk to anyone, and tell no one where you’ve been. You’ll meet a couple

of FBI agents at the front door, who will give you instructions.

Maguire nodded

along.

“OK,” he said.

Outside Richter’s office, he shot a

glance at Anna. She winked. Moments later, Maguire walked

off an elevator on the first floor, turned a corner, and trudged down a

half-dozen steps, where he badged through the security turnstiles. Maguire

stepped across the agency’s iconic lobby, with its massive seal -- the head of

an eagle atop a sixteen-point compass -- laid into cold granite. There he found

two men standing in business suits. They flashed their credentials and asked

Maguire to follow them. All moved for the front doors.

Maguire found

himself seated in the rear of a plain-Jane bureau car, which rolled out of the

Langley compound into the northern Virginia suburbs. The ride was a blur of

bright green tree canopies, the engine’s drone, and a pair of FBI agents

attempting to break the tension with small talk.

Maguire heard one

of them ask him, “Whattaya think?”

“Well,” he said,

“I’m not used to riding in the back of a police car. It doesn’t fill me with

confidence. But I’m not cuffed yet.”

The agents told

him to relax. But Maguire, who had served on some of America’s most dangerous

streets in Baltimore, didn’t feel fine. When he was a cop, he’d been the one

putting perps in squad cars for the free rides to jail.

Soon the car

pulled up to a house deep in the suburbs, in a neighborhood Maguire didn’t

recognize. The FBI agents led him inside, where he spied a few others. Only

then did he fully understand where he’d been taken. He was in a bureau safe house. Agents brought him

to a bedroom, where he found an older man sitting behind a desk. The man hooked

him up to a polygraph with a confidence that only contributed to Maguire’s

unease.

Maguire

was accustomed to routine lie-detector tests. The agency wired its clandestine

officers to the box every few years, usually when they rotated through

headquarters, for single-issue polygraphs. Tests on the box were supposed to

help the agency detect turncoats in their midst. But rarely, if ever, did they

do anything of the kind.

Polygraph

operators place their subjects on a pad that can sense the clenching of their

sphincters, a device known by those who’ve sat on them as the “whoopee

cushion.” Maguire took his seat, his sphincter already tight enough to crush

walnuts. There the older agent connected him to a series of wires that measured

his breathing, blood pressure, pulse, and perspiration.

Polygraphers

always begin with slam-dunk queries -- “Is your name John R. Maguire?” --

before asking the subject to respond with a deliberate lie or two. These are

called control questions. For instance, the operator might tell a subject to

deliberately lie to a question such as, “Have you ever stolen anything?” Few

humans can honestly answer that with a no. When the respondent lies, the

polygraph’s stylus jiggles, giving the operator a benchmark for later deceptive

answers. Relevant questions follow.

Maguire dreaded

the first such query, which he imagined would go something like this: “Did you,

or did you not, authorize or participate in an attempt to overthrow the regime

in Iraq?”

He

tried to think ahead. He knew he hadn’t done anything illegal; the actions of

CIA officers in the field assigned to wresting Saddam Hussein from power were

fully authorized by senior agency officials like Richter. The White House was

distancing itself, but officials in the Clinton administration had been briefed

directly. Maguire decided that if the agent running the box posed even one

question about Iraq, he’d politely ask to speak with his lawyer.

The genteel

polygraph operator, perhaps sensing Maguire’s inner tumult, told him to relax,

everything was going to be OK. And sure enough, when the older man eventually

got around to asking the moment-of-truth questions, they were all about Russia

and Russian intelligence. Maguire breathed easier. He had no operational

history with the Russians, and if Moscow’s foreign intelligence officers had

anything on him, it would have been thin, dated, and focused on his

paramilitary past. As far as he knew, he’d never been a target of the KGB or

the SVR.

The polygraph took

about ninety minutes, and when the operator told him he’d passed, one of the

FBI agents led Maguire into another room in the house, which clearly served as

a hub for an investigation of some kind. They seated him at a desk, where he

signed formal papers by which he swore not to divulge any of the classified

information he was about to hear. The agents told him they were from Squad

NS-34, a counterintelligence unit based in the Washington Metropolitan Field

Office. They occupied a dilapidated building at the confluence of the Potomac

and Anacostia Rivers, a

gritty corner of DC known as Buzzard Point. Your Watchman knows the area

well.

Maguire spied a

photograph of a bearded man on the wall. It appeared to be an official CIA

photo. He didn’t recognize the face.

“You’ve

been selected for this position,” one of the agents told Maguire. “We have

another Ames, and we have to catch him.”

The FBI and CIA

had handpicked Maguire to help catch this new mole. His background as a cop,

and his experience testifying in court, made him a shoo-in as a candidate to

help the bureau gather evidence inside CIA headquarters and neuter their suspect: Harold James “Jim”

Nicholson.

Agents explained

that Jim, whom Maguire had never met, was now in his sixteenth year as a CIA

operations officer. He taught tradecraft at The Farm, a plum job given to spies

who’d proven themselves in the field. Jim, he learned, was a single dad with

primary custody of his three kids: Son Jeremi was headed to college; daughter

Star and younger son Nathan lived in a two-story government house at Camp

Peary, but were soon moving to the family town house in Burke, Virginia.

Maguire knew The

Farm well. He had taken his five-month career trainee course and extensive

paramilitary training on its grounds before being sent to a CIA demolition

school in a covert redoubt in the mid- Atlantic tidewaters. There, he had

learned how to build and dismantle all manner of explosives.

The agents had cooked up a scheme for senior CIA

officials to call Jim back from The Farm and assign him as a branch chief in the

Counter- terrorist Center, or CTC, in the Original Headquarters Building. (It

was later renamed the Counterterrorism Center.) Maguire would

apply to work as the deputy branch chief under Jim. FBI investigators hoped Jim

would pick Maguire over other applicants for the position. If all went

according to plan, Maguire would take the office next to Jim’s. The FBI- CIA

team would covertly supervise Maguire’s undercover tilt against his own boss, a

spy-versus-spy operation in the bosom of CIA headquarters.

No such investigation had ever been run under the roof at

Langley.

Investigators knew

Jim would interview several experienced CIA officers for the position of deputy

branch chief, his top subordinate. But they secretly stacked the deck with

Maguire, who had much stronger credentials than the others. Maguire was a founding member of

the CTC, a distinction marking him as a “plank holder.” He knew the

territory, having worked against Middle East terrorists for years.

Maguire was a good

spy, and the kind of guy you’d join for a few rounds of bourbon. But

investigators looking to bring Jim to justice were more interested in the

skills Maguire had acquired in his former life as a Baltimore City cop. He had

worked long hours in the violent corners of Charm City’s neighborhoods, streets later made famous in the

TV series, “The Wire”. Maguire worked well with prosecutors and logged

countless hours on witness stands.

He

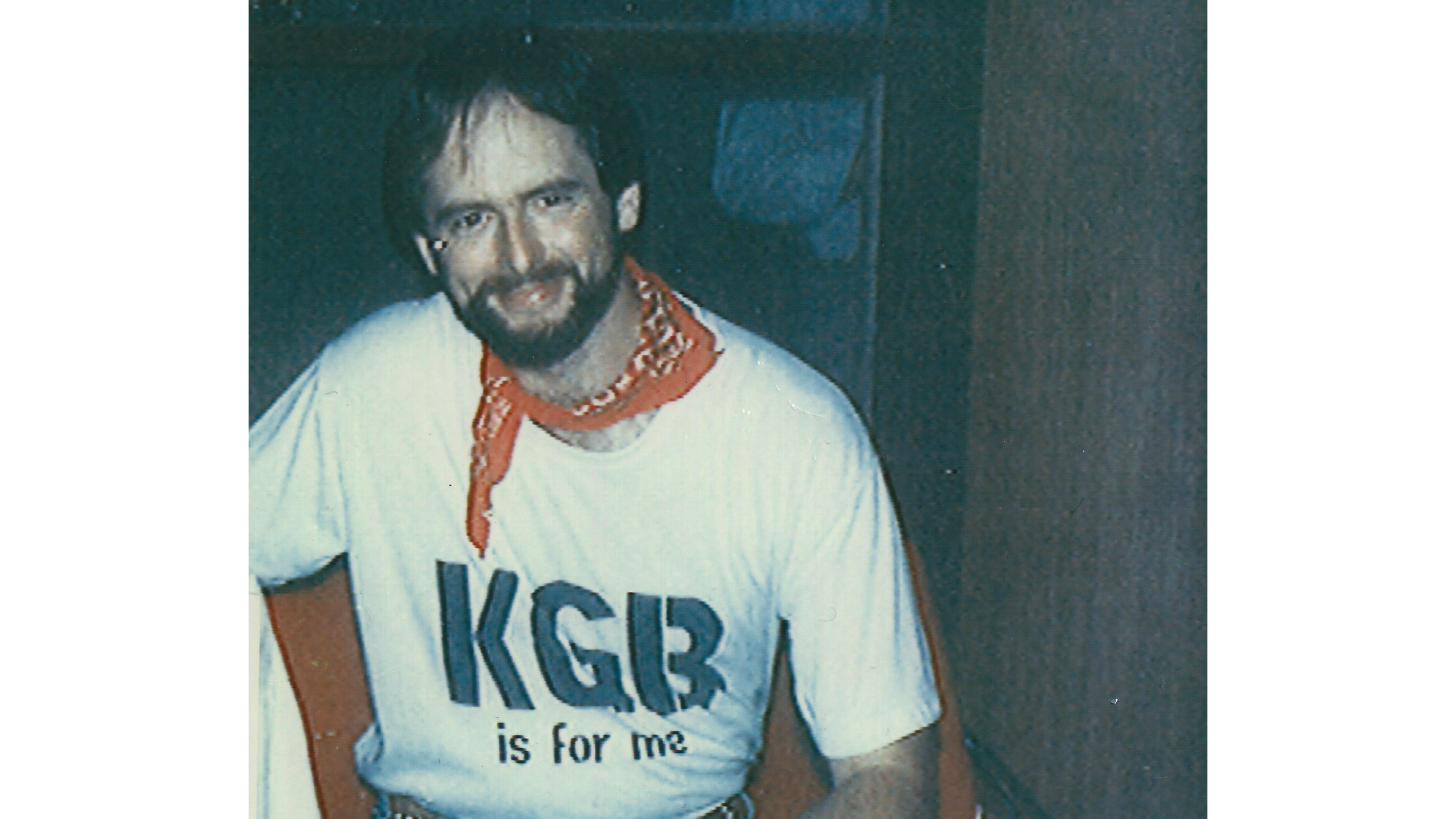

walked into Room 6E2911 that summer for his interview with Jim Nicholson, pictured above. They took seats

in Jim’s office, which sat behind a heavy cipher- locked door on the far end of

a bullpen of case officers and career trainees. Much was revealed to Maguire

when he sneaked a glance at the I-love-me walls flanking his prospective boss’s desk. Everywhere

he looked there were framed photos of Jim, certificates, military awards, and

other commendations. It was clear the guy was smart, and liked himself. A lot.

“He was a good

interviewer,” Maguire recalled. “He was looking for somebody who knew what they

were doing, understood the target, somebody he could rely on—somebody he could

use.”

Maguire recited

his bona fides to Jim, explaining that he was an experienced hand, good at

cultivating assets, and was happy to put some of his best Middle East contacts

back on the payroll. He said his assets could help Jim’s branch identify and

break up cells of Islamic fundamentalists bent on killing Americans or

otherwise threatening U.S. security.

Jim wondered how a

talented case officer had fallen so far, ending up in HR. So Maguire leveled

with him. He’d pissed off Richter, who had cast him into the abyss. Maguire

joked about wanting to jump out the window, but HR was on the second floor and

he’d only break a bunch of bones. The two veteran spies shared a laugh. Jim

knew Richter, and he’d certainly faced his own hassles with agency bureaucracy.

But although he appreciated Maguire’s dire predicament, he couldn’t promise him

anything.

Maguire walked out

thinking he’d nailed the interview. But he knew Jim wasn’t about to hire him

until he’d worked the hallway file: the informal vetting of prospective

employees in the corridors, back offices, and massive food court on the first

floor of the agency’s Original Headquarters Building. There were plenty of

people inside who would vouch for Maguire’s native talent as a spy, and a

couple who could f**k things up with a mixed review.

Investigators

crossed their fingers. Without somebody working for them inside Jim’s locked

office, there was no telling how many of the nation’s most closely guarded

secrets Jim would purloin and sell to the Russians during daylight duties in

the CTC.

Weeks

later, Maguire picked up an envelope addressed to him at work. Inside was a

directive from the personnel division. The CIA bureaucracy was so big that if

you moved from one part of the agency to another, even laterally, someone had

to create paperwork to update your salary and benefits. The papers told Maguire

to report immediately as deputy branch chief in the CTC under Jim Nicholson.

This was his passport out of the Death Star, and a chance to try his spy skills against one of the

shrewdest characters he’d ever met.

Not long after

Maguire got word he would be working for Jim, Redmond called him for a meeting in one of the

agency’s “black rooms,” offices with no descriptors on the door, just cipher

locks. There he found himself buttonholed by the veteran counterintelligence

supervisor who had headed

the long-in-coming apprehension of Rick Ames. Redmond confided in Maguire that

if he performed well in his undercover role, he’d serve his country admirably

and notch a major milestone in his career.

“If you f**k it

up,” he said, “you’re finished. So don’t f**k it up.” Below, Jim Nicholson, was arrested at Dulles Int'l Airport in 1996.

No comments:

Post a Comment