All Muslims acknowledge that God is the only one who

knows the future. But they also agree that he has offered us a peek at it, in

the Koran and in narrations of the Prophet. The Islamic State differs from

nearly every other current jihadist movement in believing that it is written

into God’s script as a central character. It is in this casting that the

Islamic State is most boldly distinctive from its predecessors, and clearest in

the religious nature of its mission.

In broad strokes, al-Qaeda acts like an underground

political movement, with worldly goals in sight at all times—the expulsion of

non-Muslims from the Arabian peninsula, the abolishment of the state of Israel,

the end of support for dictatorships in Muslim lands. The Islamic State has its

share of worldly concerns (including, in the places it controls, collecting

garbage and keeping the water running), but the End of Days is a leitmotif of

its propaganda. Bin Laden rarely mentioned the apocalypse, and when he did, he

seemed to presume that he would be long dead when the glorious moment of divine

comeuppance finally arrived. “Bin Laden and Zawahiri are from elite Sunni

families who look down on this kind of speculation and think it’s something the

masses engage in,” says Will McCants of the Brookings Institution, who is

writing a book about the Islamic State’s apocalyptic thought.

During the last years of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, the

Islamic State’s immediate founding fathers, by contrast, saw signs of the end

times everywhere. They were anticipating, within a year, the arrival of the

Mahdi—a messianic figure destined to lead the Muslims to victory before the end

of the world. McCants says a prominent Islamist in Iraq approached bin Laden in

2008 to warn him that the group was being led by millenarians who were “talking

all the time about the Mahdi and making strategic decisions” based on when they

thought the Mahdi was going to arrive. “Al-Qaeda had to write to [these

leaders] to say ‘Cut it out.’ ”

For certain true believers—the kind who long for epic good-versus-evil

battles—visions of apocalyptic bloodbaths fulfill a deep psychological need. Of

the Islamic State supporters I met, Musa Cerantonio, the Australian, expressed

the deepest interest in the apocalypse and how the remaining days of the

Islamic State—and the world—might look. Parts of that prediction are original

to him, and do not yet have the status of doctrine. But other parts are based

on mainstream Sunni sources and appear all over the Islamic State’s propaganda.

These include the belief that there will be only 12 legitimate caliphs, and

Baghdadi is the eighth; that the armies of Rome will mass to meet the armies of

Islam in northern Syria; and that Islam’s final showdown with an anti-Messiah

will occur in Jerusalem after a period of renewed Islamic conquest.

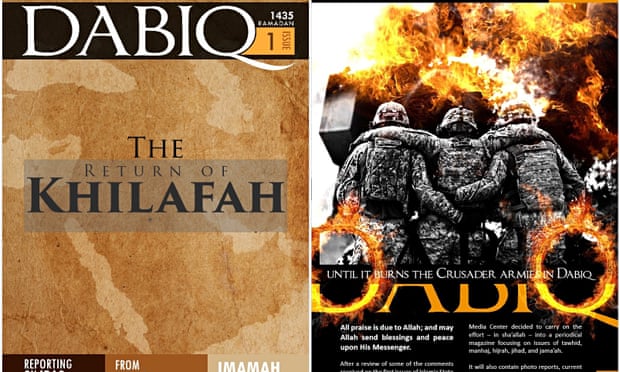

The Islamic State has attached great importance to the

Syrian city of Dabiq, near Aleppo. It named its propaganda magazine after the

town, and celebrated madly when (at great cost) it conquered Dabiq’s

strategically unimportant plains. It is here, the Prophet reportedly said, that

the armies of Rome will set up their camp. The armies of Islam will meet them,

and Dabiq will be Rome’s Waterloo or its Antietam.

“Dabiq is basically all farmland,” one Islamic State

supporter recently tweeted. “You could imagine large battles taking place

there.” The Islamic State’s propagandists drool with anticipation of this

event, and constantly imply that it will come soon. The state’s magazine quotes

Zarqawi as saying, “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will

continue to intensify … until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.” A recent

propaganda video shows clips from Hollywood war movies set in medieval

times—perhaps because many of the prophecies specify that the armies will be on

horseback or carrying ancient weapons.

Now that it has taken Dabiq, the Islamic State awaits the

arrival of an enemy army there, whose defeat will initiate the countdown to the

apocalypse. Western media frequently miss references to Dabiq in the Islamic

State’s videos, and focus instead on lurid scenes of beheading. “Here we are,

burying the first American crusader in Dabiq, eagerly waiting for the remainder

of your armies to arrive,” said a masked executioner in a November video,

showing the severed head of Peter (Abdul Rahman) Kassig, the aid worker who’d

been held captive for more than a year. During fighting in Iraq in December,

after mujahideen (perhaps inaccurately) reported having seen American soldiers

in battle, Islamic State Twitter accounts erupted in spasms of pleasure, like

overenthusiastic hosts or hostesses upon the arrival of the first guests at a

party.

The Prophetic narration that foretells the Dabiq battle

refers to the enemy as Rome. Who “Rome” is, now that the pope has no army,

remains a matter of debate. But Cerantonio makes a case that Rome meant the

Eastern Roman empire, which had its capital in what is now Istanbul. We should

think of Rome as the Republic of Turkey—the same republic that ended the last

self-identified caliphate, 90 years ago. Other Islamic State sources suggest

that Rome might mean any infidel army, and the Americans will do nicely.

After its

battle in Dabiq, Cerantonio said, the caliphate will expand and sack Istanbul.

Some believe it will then cover the entire Earth, but Cerantonio suggested its

tide may never reach beyond the Bosporus. An anti-Messiah, known in Muslim

apocalyptic literature as Dajjal, will come from the Khorasan region of eastern

Iran and kill a vast number of the caliphate’s fighters, until just 5,000

remain, cornered in Jerusalem. Just as Dajjal prepares to finish them off,

Jesus—the second-most-revered prophet in Islam—will return to Earth, spear

Dajjal, and lead the Muslims to victory.

“Only God

knows” whether the Islamic State’s armies are the ones foretold, Cerantonio

said. But he is hopeful. “The Prophet said that one sign of the imminent

arrival of the End of Days is that people will for a long while stop talking

about the End of Days,” he said. “If you go to the mosques now, you’ll find the

preachers are silent about this subject.” On this theory, even setbacks dealt

to the Islamic State mean nothing, since God has preordained the

near-destruction of his people anyway. The Islamic State has its best and worst

days ahead of it.

One way to un-cast the Islamic State’s

spell over its adherents would be to overpower it militarily and occupy the

parts of Syria and Iraq now under caliphate rule. Al‑Qaeda is ineradicable

because it can survive, cockroach-like, by going underground. The Islamic State

cannot. If it loses its grip on its territory in Syria and Iraq, it will cease

to be a caliphate. Caliphates cannot exist as underground movements, because

territorial authority is a requirement: take away its command of territory, and

all those oaths of allegiance are no longer binding. Former pledges could of

course continue to attack the West and behead their enemies, as freelancers.

But the propaganda value of the caliphate would disappear, and with it the

supposed religious duty to immigrate and serve it. If the United States were to

invade, the Islamic State’s obsession with battle at Dabiq suggests that it

might send vast resources there, as if in a conventional battle. If the state

musters at Dabiq in full force, only to be routed, it might never recover.

Given

everything we know about the Islamic State, continuing to slowly bleed it,

through air strikes and proxy warfare, appears the best of bad military

options. Neither the Kurds nor the Shia will ever subdue and control the whole

Sunni heartland of Syria and Iraq—they are hated there, and have no appetite

for such an adventure anyway. But they can keep the Islamic State from

fulfilling its duty to expand. And with every month that it fails to expand, it

resembles less the conquering state of the Prophet Muhammad than yet another

Middle Eastern government failing to bring prosperity to its people.

The

humanitarian cost of the Islamic State’s existence is high. But its threat to

the United States is smaller than its all too frequent conflation with al-Qaeda

would suggest. Al-Qaeda’s core is rare among jihadist groups for its focus on

the “far enemy” (the West); most jihadist groups’ main concerns lie closer to

home. That’s especially true of the Islamic State, precisely because of its

ideology. It sees enemies everywhere around it, and while its leadership wishes

ill on the United States, the application of Sharia in the caliphate and the

expansion to contiguous lands are paramount. Baghdadi has said as much

directly: in November he told his Saudi agents to “deal with the rafida [Shia]

first … then al-Sulul [Sunni supporters of the Saudi monarchy]

… before the crusaders and their bases.”

Baghdadi is Salafi. The term Salafi has

been villainized, in part because authentic villains have ridden into battle

waving the Salafi banner. But most Salafis are not jihadists, and most adhere

to sects that reject the Islamic State. They are, as Haykel notes, committed to

expanding Dar al-Islam,

the land of Islam, even, perhaps, with the implementation of monstrous

practices such as slavery and amputation—but at some future point. Their first

priority is personal purification and religious observance, and they believe

anything that thwarts those goals—such as causing war or unrest that would

disrupt lives and prayer and scholarship—is forbidden.

The

Islamic State's (ISIS) mass execution of Egyptian Christians, pictured above, is the latest sign

that ISIS is pointing its sword against not just the West but the rest of the

Arab world -- drawing the region into a spreading war.

The U.S. coalition started last fall as a U.S.-led airstrike campaign included several Gulf states, and Jordan. Not only have a host of western nations since joined to offer at least financial support, but several other countries in the Middle East and North Africa are now launching their own military campaigns.

On Monday, Egyptian warplanes struck at ISIS militants in Libya, in retaliation for the mass execution of Coptic Christians from Egypt. The airstrikes reportedly were coordinated with the Libyan government.

Syria's Assad regime has been fighting ISIS from the start. And Jordan, a U.S. ally, has escalated its role in the coalition after a captured Jordanian pilot was burned alive by the Islamic State.

The distinct campaigns have raised questions about the direction of the anti-ISIS coalition and alliances in the region.

"It's much more like Game of Thrones, and much less like a seriously thought-through strategy against a regional opponent," said Danielle Pletka, senior vice president for foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

The U.S. coalition started last fall as a U.S.-led airstrike campaign included several Gulf states, and Jordan. Not only have a host of western nations since joined to offer at least financial support, but several other countries in the Middle East and North Africa are now launching their own military campaigns.

On Monday, Egyptian warplanes struck at ISIS militants in Libya, in retaliation for the mass execution of Coptic Christians from Egypt. The airstrikes reportedly were coordinated with the Libyan government.

Syria's Assad regime has been fighting ISIS from the start. And Jordan, a U.S. ally, has escalated its role in the coalition after a captured Jordanian pilot was burned alive by the Islamic State.

The distinct campaigns have raised questions about the direction of the anti-ISIS coalition and alliances in the region.

"It's much more like Game of Thrones, and much less like a seriously thought-through strategy against a regional opponent," said Danielle Pletka, senior vice president for foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

ISIS-aligned

militants are battling on many fronts in the region boosting its already-robust

recruitment.

The multiple fronts, though, create challenges for the Obama administration. Iran is aiding Shiite militias now battling ISIS militants on the ground in Iraq thus increases Iran's already growing influence in that country.

Retired Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer, a former military intelligence officer now with the London Center for Policy Research, said: "Egypt jumping into Libya is not part of the [U.S.] plan." Shaffer said his group is urging the creation of a single "comprehensive treaty organization" -- a standing coalition of countries in the region, which he describes as a sort of "Arab NATO." Such a group, he said, could organize against ISIS and plan for establishing post-ISIS governance in areas where there is none. This could include Jordan, Egypt and several other governments all fighting a common enemy, which he stressed as critical. "If everyone is in charge, no one is in charge," he said, describing the current patchwork of local battles in the region.

Matthew Levitt, counterterrorism analyst with The Washington Institute, described the strikes in Libya as a separate issue from other Islamic State battles, and one fed by the severe instability in that country. "It's a problem for Egypt, because they're right next door," he noted.

The multiple fronts, though, create challenges for the Obama administration. Iran is aiding Shiite militias now battling ISIS militants on the ground in Iraq thus increases Iran's already growing influence in that country.

Retired Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer, a former military intelligence officer now with the London Center for Policy Research, said: "Egypt jumping into Libya is not part of the [U.S.] plan." Shaffer said his group is urging the creation of a single "comprehensive treaty organization" -- a standing coalition of countries in the region, which he describes as a sort of "Arab NATO." Such a group, he said, could organize against ISIS and plan for establishing post-ISIS governance in areas where there is none. This could include Jordan, Egypt and several other governments all fighting a common enemy, which he stressed as critical. "If everyone is in charge, no one is in charge," he said, describing the current patchwork of local battles in the region.

Matthew Levitt, counterterrorism analyst with The Washington Institute, described the strikes in Libya as a separate issue from other Islamic State battles, and one fed by the severe instability in that country. "It's a problem for Egypt, because they're right next door," he noted.

alliance remived Mubarak from power in Egypt and Assad in Syria.

The conflict with ISIS has temporarily drawn attention away from what once was the No. 1 enemy in the region, Israel. You will notice I said temporarily because I believe the Psalm 83 War is on the horizon. Even before the rise of ISIS some Arab states in the region, for example Saudi Arabia, were beginning to -- quietly -- work with Israel on various challenges including Iran. Now with ISIS the singular force uniting a region notoriously riven by tribal, religious and territorial differences, Israel is on the sidelines. "This is actually not about Israel, for the first time in a long time," Levitt said. He suggested it best for Israel not to play any active role in the current conflict but said the reality is the Gulf states are now realizing "that not every evil in the world ... has to do with Israel." Pletka said "They and the Israelis see the region through the same prism." "This is a major, tectonic shift," Pletka said. I do not agree with Pletka, Arab the hatred for the Jews is implacable and Arab hatred will not go away until the Arabs are utterly defeated.

The Islamic State, meanwhile, continues to incite surrounding countries, chiefly through the tactic of horrific executions.

The video released online over the weekend showed 21 Egyptian victims kneeling on a beach, before being beheaded. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi quickly vowed revenge, saying the whole world is in a "fierce battle with extremist groups."

Both the Egyptian government and Libya's fragile state are facing internal threats from militants claiming loyalty to ISIS. Egypt already is battling ISIS militants in the Sinai Peninsula, and the airstrikes in neighboring Libya mark an expansion of that fight.

"Clearly, this is a global jihad right before our eyes," said retired U.S. Gen. Jack Keane.

The White House noted that the killing "is just the most recent of the many vicious acts perpetrated by ISIL-affiliated terrorists against the people of the region, including the murders of dozens of Egyptian soldiers in the Sinai, which only further galvanizes the international community to unite against ISIL."

The White House is hosting a summit later this week on "countering violent extremism."

No comments:

Post a Comment