| Barry Chamish |

Friends, just a reminder the Watchman supports Israel as a Biblical mandate from God. I believe the "Fig Tree" - Israel blossomed in 1948 but Israel and the Jews have not borne fruit yet. God has promised He will save the Jews and He will keep His promise. Labor Zionists are secular and many cases Godless and have committed evil acts against their fellow Jews. Barry Chamish and his Jewish have suffered at the hands of the Labor Zionists.

By Barry Chamish

In 1932, how many organizations in Germany represented German Jewry? Over 250.

In 1932, how many organizations in Germany represented German Jewry? Over 250.

In 1933, how many? One, Labour

Zionism.

First, Rabbi Antelman's account

continues. To corrupt the Jews, the Frankists adopted, at first, a humane

policy of sorts. With Rothschild money and Jesuit power, the so-called

Enlightenment was initiated by the German Jewish apostate Moses Mendelsohn.

Napoleon was financed to liberate the Jews wherever he conquered and from

Germany, the Reform and Conservative movements were financed to further dilute

the faith and introduce totally foreign concepts to their congregations. But

the pace wasn't fast enough. The ornery Jews just weren't cooperating with

evil, so those stubbornly accepting Torah morality would have to be removed

permanently and only those practising Shabbatainism (Sabbatean) would be

permitted to survive.

| Shabbatai Zvi

This

portion of the article was written by The Watchman. Sabbatai Zvi was a

Sephardic Rabbi and kabbalist who claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish

Messiah. He was the founder of the Jewish Sabbatean movement. At the age of

forty, he was forced by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV to convert to Islam.

|

Of great impact was the messianic movement that arose

around Shabbatai Zvi (1626-1672). In fact, in its scope and intensity the

so-called Sabbatian movement has no parallel in Jewish history. It drew its

strength from traditional Jewish hopes for political and spiritual redemption;

but the specific catalyst for it was the kabbalistic interpretation of exile

and redemption, widely diffused by the mid-seventeenth-century, with its assumption

that redemption was imminent.

The figure

around whom the movement crystallized was a rather unlikely one. Shabbatai Zvi

was born to an affluent family in Izmir (Smyrna) in 1626. Shabbatai and

his followers claimed that he was born on the Ninth of Ab (Tisha be-Av), the

fast day commemorating the destruction of the Temples in Jerusalem – a day on

which, according to Jewish lore, the Messiah was to be born. He received a

traditional rabbinic education and was recognized as a gifted student. In

adolescence, he turned to the study of Kabbalah, in which he became proficient.

At least superficially, he seemed destined for a career as a rabbinic scholar;

but his behavior became increasingly erratic, with periods of depression

alternating with states of exaltation. Some Smyrna Jews were strongly drawn to

him and inspired by his religious utterances. However, his repeated claims to

be the Messiah, and his utterances of the ineffable name of God, led the rabbis

of Smyrna to banish him from that city in the early 1650s.

For years he traveled about the

eastern Mediterranean, sometimes manifesting normal behavior, at others

performing bizarre acts in a state of ecstasy. In 1664 Shabbatai married a

woman named Sarah, whose doubtful reputation may have given a symbolic meaning

to the marriage: He may have believed he was following in the footsteps

of the prophet Hosea. At the same time, he was troubled by his compulsions to

violate Jewish law. His hopes of a “cure” were stirred when he learned of a Jew

who had appeared in Gaza, who claimed he could cure the soul. It was Shabbatai’s

fateful meeting with Nathan of Gaza, whom he sought out in order to “find a tikkun and peace for his soul,” as one

report put it, that set the movement in motion.

By the time

the two men met in Gaza in 1665, the young kabbalist Nathan of Gaza had already

heard of Shabbetai Zvi, and was soon convinced that he was the Messiah. At

Nathan’s urging, Shabbetai revealed himself as such. Some of the leading

rabbinic figures in Jerusalem denounced him, however, and he was banished from

Jerusalem. But Nathan of Gaza called for a mass movement of repentance to

hasten the redemption, attracting a large following. This penitential movement,

in itself a desirable development, may have posed difficulties for the rabbis

of Jerusalem, who took no further active steps to suppress the movement, even

when their opinion was sought.

Reports that

the Messiah had appeared in the person of Shabbatai Zvi spread quickly across

the Ottoman Empire and Europe, with rumors of miracles and wild predictions

accompanying the facts. Nathan of Gaza acted vigorously to promote the

movement, sending letters, composing special liturgies, and prescribing fasts.

Swept up in the excitement were not only ordinary men and women, but also rabbinic

scholars and communal leaders. In Smyrna, where Shabbatai Zvi arrived in the

fall of 1665, a heady penitential movement developed, fueled by Shabbatai’s

performance of “strange acts” – symbolic behaviors that were often in violation

of Jewish law, such as eating forbidden foods and uttering the ineffable name.

As letters

reached Europe and North Africa with reports about the movement (reports that

were often embellished), enthusiasm among Jews throughout the diaspora reached

a fever pitch. In the year 1666, at the movement’s height, pamphlets

publicizing the unfolding of the redemptive scenario were published, and

fervent believers undertook penitential fasts and extreme acts of

self-affliction. Some Jews sold their property, with the intention of journeying

to the Land of Israel. The commotion was followed closely in Christian circles,

especially among Christian millennians, who were instrumental in the publication

of letters, and pamphlets and broadsheets in Italian, German, Dutch, and

English. To be sure, not everyone reacted with enthusiasm. In the Jewish world,

in fact, many doubted the “news.” Tensions had developed early on between

“believers” and “infidels”; but as the movement gained momentum, opponents were

frightened into silence by punitive measures against them.

In 1666,

Shabbatai Zvi traveled to Constantinople (Istanbul), seeking to meet with the

Sultan. According to some sources, his goal was to persuade the Sultan to

give Jerusalem to the Jews. The Sultan, probably disturbed by the disorder

caused by the movement, had Shabbatai Zvi arrested and sent to

Gallipoli. His imprisonment, however, did not diminish the excitement of

his followers, many of whom flocked to visit him in prison. In a state of

ecstasy, Shabbatai Zvi declared the solemn fast day of the Ninth of Av a

holiday of celebration.

Accounts

differ about exactly how events took a turn in September, 1666. It seems likely

that the Ottoman authorities wanted to bring the alarming popular movement to

an end. In any case, Shabbatai Zvi was taken to Adrianople, where he was given

the choice of being put to death or converting to Islam. Fatefully, he agreed

to convert, and took the name Aziz Mehmed Effendi.

News of the

“messiah’s” apostasy spread rapidly, stunning the Jewish world. For most Jews,

an apostate Messiah was an impossibility, and it became the task of the

rabbinic and communal leadership to restore a sense of order and everyday

purpose. The strategy adopted was one of studied forgetfulness: The movement

was assigned to oblivion.

Not everyone,

however, accepted this course. Nathan of Gaza, entirely invested in the

movement, acted to keep it alive, declaring that the apostasy was a deep

mystery, which he proceeded to explain in kabbalistic terms as part of the

process of redemption. He and other followers of Shabbetai Zvi continued to

adhere to a paradoxical theology that relied on reinterpretation of classic

Jewish texts. The rabbinic establishment, of course, condemned such ideas as

heretical.

As for Shabbatai

Zvi, he drew around him a group of “believers” in Adrianople who in his

footsteps had also accepted Islam outwardly. He continued to inspire his

followers with his mystical mission, and died in 1676, apparently still

persuaded of his covert messianic role.

The story of

the Sabbatian movement after Shabbatai Zvi’s death is long and interesting,

but largely marginal. Sabbatanism groups continued to be active in Turkey,

Italy, and Poland. One of the most interesting of the defenders of Sabbatanism

after Shabbetai Zvi’s death was Abraham Cardoso, an ex-converso whose

Sabbatean theology, probably influenced by Catholicism, foresaw the return of

Shabbetai Zvi to realize the final redemption. Sabbateanism had not

entirely died out even in the late eighteenth century.

Barry Chamish wrote this portion of the article. Yes, in the 2000 years of European Jewish history there were pogroms, Crusades and Inquisitions, the latter aided and abetted by the Jesuits. But compared to what happened from the 1880s on, life was a tolerable picnic. The turning point in the final war against the Jews was the founding of Zionism by the Shabbataians. The final aim of the movement was to establish a Shabbataian state in the historical land of the Jews, thus taking over Judaism for good.

To foment the idea, life had to made

so intolerable for Europe's Jews, that escape to Palestine would appear to be

the best option. The Cossack pogroms were the first shot in this campaign and

for them, the Frankists turned to the Jesuits and their influence over the

Catholic Church. The Jesuits had done more to spread communism, beginning with

their feudal communes in South America, and now they wanted to punish the

anti-papists of Europe by imprisoning them behind communal bars. The deal was

simple: The Jesuits provided the Cossacks, the Frankists, the communists. And

naturally, the Rothschilds would provide the moolah.

Once the situation turned foreboding, the German-writing intellectuals took over. In Vienna in 1885, the journalist Natan Birnbaum fired the opening salvo which successfully planted the fast-growing seeds of Zionism. He was followed by another Vienna writer, Peretz Smoleskin, who provided more intellectual justification for returning to a safe home in Israel. However, neither man had the charisma of still another Vienna writer, Theodore Herzl. He could rally the masses as neither of them could and he was chosen to be the spokesman and symbol of the movement.

Read any honest biography of Herzl and

the same quandary appears. Herzl claimed he wrote the Judenstaat (The Jewish State) one summer in

Paris. But Herzl wasn't in Paris when he said he wrote the most influential

book of Zionism. It had to have been written for him. Anyone who reads Herzl's

dreadful plays, has to doubt his sudden departure from literary mediocrity.

In 1901, Herzl appeared in Britain

where he was not well received. We are told he backed another option, creating

a Jewish sanctuary in British - controlled East Africa. If the idea caught on,

it would neutralize the Shabbataians' game plan. Herzl died not long after and

not one biography of him tells us how. He entered a Paris sanatorium for a not

known condition and never came out alive.

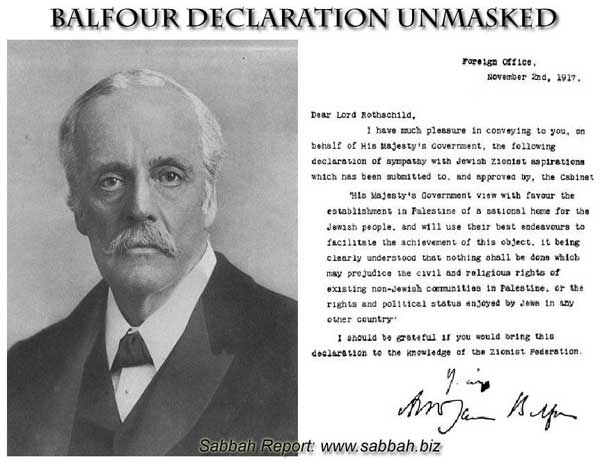

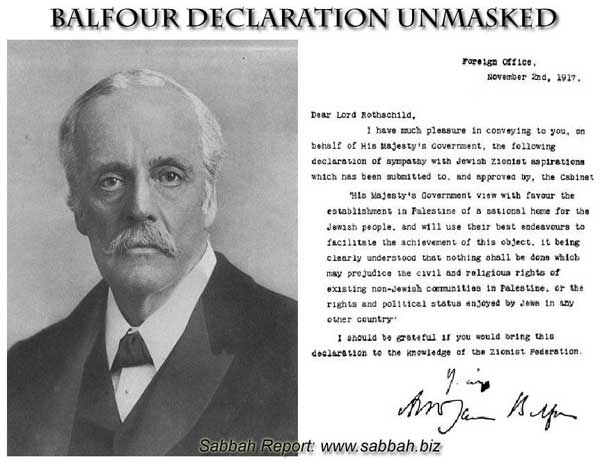

This was highly fortunate for the

British Freemasons doing the Shabbataians' bidding, for they replaced Herzl

with one of their own, a German-educated Jew named Chaim Weizmann. In time, a

cockamamie legend was fabricated involving the Balfour declaration creating a

Jewish homeland in Palestine as a reward for Weizmann finding a way to make

acetone for explosives from dried up paint. Not one explosion in World War One

came from this magic process. But the British took great pains to capture

Palestine from the Turks and appoint the leaders of the upcoming Shabbataian

state.

Meeting in London during the War,

Weizmann and Balfour had to deal with the problem of the people already living

in Palestine, most of whom were religious Jews, who were the majority in such

major centers as Jerusalem, Sfat and Tiberius. The myth of an ancient

Palestinian Arab indigenous population is belied by any number of reports by

visitors as talented as Twain and Balzac, who accurately noted the paucity of

Arabs in the land during the 19th century. The later economic success of the

new enterprise drew hundreds of thousands of Arabs from as far away as Iraq to

the region with consequences the Illuminati were possibly well aware of.

To neutralize the religious Jews, many of whom had been living in the land since antiquity, Balfour and Weizmann inducted Rabbi Avraham Kook into the fold and after the war, he was appointed the first Chief Rabbi of the enterprise, while Weizmann was made the first head of the Jewish Agency. Kook proceeded to strip the landed Orthodox Jews of their real estate and political rights, while introducing a new concept into Judaism; the purity of land redemption. His philosophy was based on profound historical truth, nonetheless, his followers don't understand how he and they are playing out the Shabbataian nightmare.

Stage one was complete. Now the real

business at hand was revved up. Rabbi Antelman proves that the American

President Woodrow Wilson was thoroughly corrupted by the Frankists through

their agent Colonel House.

It was Wilson who put an end to America's open

immigration policy. Until then, despite all their despair, most Eastern

European Jews rejected Palestine as an escape route, the majority choosing

America as their destination. From now on very few would enjoy that option. It

would have to be Palestine or nowhere.

We now jump to 1933. Less than 1% of

the German Jews support Zionism. Many tried to escape from Naziism by boat to

Latin and North American ports but the international diplomatic order was to

turn them back. Any German Jew who rejected Palestine as his shelter would be

shipped back to his death.

By 1934, the majority of German Jews got the message and turned to the only Jewish organization allowed by the Nazis, the Labour Zionists. For confirmation of the conspiracy between them and Hitler's thugs read The Transfer Agreement by Edwin Black, Perfidy by Ben Hecht

or The Scared And The

Doomed by Jacob Nurenberger. The deal cut worked like this. The German Jews

would first be indoctrinated into Bolshevism in Labour Zionism camps and then,

with British approval, transferred to Palestine. Most were there by the time

the British issued the White Paper banning further Jewish immigration. The

Labour Zionists got the Jews they wanted, and let the millions of religious

Jews and other non-Frankists perish in Europe without any struggle for their

survival.

But not all Jews fell for the plan. A

noble alternative Zionism arose led by Zeev Jabotinsky. He led the Jews in

demanding free passage to Palestine and a worldwide economic boycott of the

Nazi regime. The Labour Zionists did all in their power to short-circuit the

opposition. First, they forced all the German Jews in Palestine to use their

assets to buy only goods from Nazi Germany. This kept the regime afloat. Then

Chaim Weizmann and his Jewish Agency employed their appointed agents in the US

to neutralize Jabotinsky and his followers using any means at their disposal.

This culminated in Jabotinsky's suspicious death in New York in 1941. Later,

Jabotinsky's most literate advocate, Ben Hecht, was run over by a truck on a

Manhattan sidewalk. His crime was being the first to widely expose the Jewish

Agency-Nazi plot.

Into this plot against the Jews we add

the Jesuits, who wished with all their hearts, to wreck the land that produced

Luther, but the Vatican's role in the Holocaust is not the focus of this

overview. We now return to America where the Jewish leadership used all their

contacts and resources to make good and certain that the unwanted

non-Shabbataian Jews of Europe never again saw the light of day.

No comments:

Post a Comment