Although 40 years in power, Muammar Gaddafi first addressed the UN

General Assembly in September 2009. Reminiscent of Fidel Castro’s speech to the

body in 1960, he went over the allotted time of 15 minutes and talked for over

an hour and a half. He advocated

for radical change in the inner workings of the UN and said that the General

Assembly should adopt a binding resolution that would put it above the

authority of the Security Council. The latter, according to Gaddafi, had failed

to prevent 65 wars since its inception and is unjust and undemocratic because

the five permanent members have all the actual power. If the General Assembly

were to be the most powerful body, however, all nations would be on equal

footing, he proclaimed, which would prevent future conflict. He ascribed

similar bias to the International Criminal Court and the International Atomic

Energy Agency, as they, just like the Security Council, are used to demonize

enemies of the global powers while their own crimes and those of their allies go

largely unnoticed. He went on to dismiss Washington’s war against Iraq,

advocated for a one state solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and

urged the General Assembly to launch investigations into the murder of Patrice

Lumumba, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and the massacres of the Israeli

army and their allies committed against the Palestinians in the Lebanese

refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in 1982 and in Gaza in 2008.[1]

The picture of Colonel Gaddafi that emerges seems

to be somewhat in conflict with that put forward by the mass media. Rather than

just another brutal power-hungry dictator who seems to be interested only in

killing his own people, it looks like he had some interesting ideas, to say the

least. It would be useful

to step away from the simplified and rhetoric-laden label of dictator for a

moment and take a deeper look into Gaddafi’s ideas and why they posed such a

great danger to the global power elite.

In his Green Book, published in 1975, Gaddafi

laid out his idea of a stateless society, which he called Jamahiriyya - a

country directly governed by its citizens without intervention from

representative bodies. According to the Green Book, states that rely on

representation are inherently repressive because individuals must surrender

their personal sovereignty to the advantage of others. With emphasis on

consultation and equality, Gaddafi therefore called into life a different

political model for Libya based on “direct democracy.” Through the

establishment of Popular Congresses and Popular Committees, representing the

legislative and executive branches respectively, Gaddafi’s political system was constructed from the

bottom up rather than from the top down. Prof. Dirk Vandewalle

scrutinised Gaddafi’s notion of popular rule in his book A

history of Modern Libya.[2] The fact that political parties outside

the system designed by Gaddafi were practically forbidden and Libyan opposition

movements were often persecuted (p. 103, 134 and 143-50); the Popular

Committees had zero power in several areas, including foreign policy,

intelligence, the army, the police, the country’s budget and the petroleum

sector (p. 104); as well as the fact that the government abolished or took over

numerous private businesses (p. 104-8) and gradually implemented a virtually

unsupervised revolutionary court system (p. 120-1) all point to the actual

authoritarian nature of the central government. Vandewalle concludes that

“The bifurcation between the Jamahiriyya’s formal

and informal mechanisms of control and political power accentuate [...] the

limited institutional control Libyan citizens have had over their country’s

ruler and his actions. In effect, unless the country’s leadership

clearly approves, there is no public control or accountability provided. [...]

Within the non-formal institutions of the country’s security organizations, the

Revolutionary Leadership makes all decisions and has no accountability to anyone.”[3]

(emphasis added)

Although Vandewalle is very critical of Gaddafi’s

rule throughout his book, he acknowledged that NATO’s Operation Unified

Protector “became a sine qua non for the rebels just to be able to maintain

their positions” and that it

was clear that “greater and more decisive NATO intervention would be needed to

defeat the loyalist side.”[4] This means that rather than a civil war between

Libyans, this was a war between Gaddafi on the one hand, who exercised all the

actual power on the international domain, and NATO on the other, which was a

necessary component in Gaddafi’s toppling. The question is: what was it

about?

War

on African independence and prosperity

From the moment he rose to power, Gaddafi’s, pictured above, anti-imperialism did not only go hand in glove with an urge for national unity

but a need to form a multilateral regional bloc as well. After Nasser died in 1970, Gaddafi

became one of the leading voices for unity under the banner or pan-Arabism, as

only then could the Arab world form a front against Israel and the West.

After a range of failed agreements of political union with Egypt, Tunisia,

Syria, Morocco and Algeria during the 1970s and 1980s, however, Gaddafi grew

increasingly frustrated over the impotence of the Arab world to make the Arab

League into a viable organization. As a result, Gaddafi reoriented to Africa, declaring in March 1999 that

“I have no time to lose talking with Arabs, I now talk pan-Africanism and

African unity.”[5] A couple of months later, he reverberated the words

of his new idol, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, often considered one of the chief

ideologues of modern pan-Africanism, calling for “the historic solution for the

[African] continent [...]: a

United States of Africa.”[6]

Africa is

kept in a structural state of underdevelopment. Recent studies have shown that

for every $1 of aid that developing countries receive, they lose $24 in net

outflows. In other words, rich countries are not developing poor countries;

poor countries are developing rich ones.[7] Hence, it would be an understatement to posit that the current

situation maintains the status quo. Rather, the global inequality gap has

significantly worsened in postcolonial times under the regimes of the IMF,

World Bank and UN. Indeed, the

distance between the richest and poorest country was already about 35 to 1 in

1950, but further rose to a staggering 80 to 1 in 1999.[8] Gaddafi

understood the potential of an Africa free of the neo-colonial grip of Western

powers. In 2005, he stated that:

“There is an attempt to promote proposals aimed at

extending aid for Africa. But when aid is linked to humiliating conditions, we

don’t want humiliation. [...] If aid is conditional and leads to compromises,

we don’t need it. [...] They are the ones who need Africa. They need its

wealth. 50% of the world’s gold reserves are in Africa, a quarter of the

world’s uranium resources are in Africa, and 95% of the world’s diamonds are in

Africa. [...] Africa is rich in unexploited natural resources, but we were [and

still are] forced to sell these resources cheaply to get hard currency. And

this must stop.”[9]

Gaddafi was not the first one to understand this.

In the second half of the 20th century, out of the dialectical relationship

between the centuries-old philosophical idea of pan-Africanism and the emerging

trend of regional economic integration worldwide, there grew the idea that

Africa, too, could only thrive through cooperation, unity and integration. The search for unity began with

the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, but over

the years, the OAU only proved to be moderately successful in its

objectives.[10] Nevertheless,

around the change of the millennium there was an emerging pattern of

independence and collaboration in Africa that might have been able to

facilitate increased African self-determination, thereby putting the continent

on a path in which it could have gradually thrown off the chains of structural

underdevelopment.[11] Although not in totality, these developments were in

large part thanks to Libya, and specifically Gaddafi. The elimination of one

man, therefore, was sufficient to disrupt the path towards African

independence, at least in the short run.

A

“United States of Africa” and the roadmap to a pan-African currency

In the first two decades after the 1969 coup, while

still being more concerned with Arab rather than African unity, Libya sought to

undermine African governments it found objectionable and provide support to

countries of its liking. In contrast, the 1990s saw a gradual shift towards

rapprochement with neighboring countries and the rest of Africa, as the

country’s foreign policy shifted towards promoting regional cohesion via more

constructive participation in multilateral arrangements and mediation in

African conflicts. In addition, to further bolster its image on the continent,

just like it dedicated large swaths of its oil revenues to pan-Arabism, the Libyan government started to

pump tens of billions of dollars in aid and investments in Africa. As a

successful vanguard of Gaddafi’s reorientation to Africa, he in 1998 convened a

meeting of Sahel and Saharan states in Tripoli, as a result of which a new

regional organization was born, the Community of Sahel and Saharan States

(CEN-SAD). Most notably, aside from promoting regional development initiatives,

the organization opposed foreign interference in African judicial issues and

condemned outside forces seeking pretexts for establishing a lasting

establishment on the continent. In 2007, CEN-SAD issued a statement from its Tripoli headquarters

categorically rejecting the US’s Africa Command (AFRICOM) and any other foreign

military presence in its member states. This was very troubling for the

US’s image in Africa, as CEN-SAD membership by then comprised roughly half of

Africa’s territory and population.[12]

It should be noted, finally, that the 2011 war in Libya was AFRICOM’s

first official war, and with its fiercest adversary out of the way, its

military exercises and overall influence on the continent since 2012 have

skyrocketed.[13] The presence of US commandos in Africa jumped from 3% of all

American troops deployed overseas in 2010 to 17 percent in 2016, and by 2017,

the US military was carrying out nearly 100 missions at any given time on the

continent.[14] In other words, Africa has become an open playing field for the

US.

“In our deliberations, we have been inspired by the

important proposals submitted by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, Leader of the Great

Al Fatah Libyan Revolution and particularly, by his vision for a strong and

united Africa, capable of meeting global challenges and shouldering its

responsibility to harness the human and natural resources of the continent in

order to improve the living conditions of its people.”[16]

So far, the AU of course has fallen far short of

becoming a “United States of Africa” as envisioned by Gaddafi. Centralization

in Europe, however, only started to be put in motion after a fierce debate in

the 1940s and 1950s between intergovernmentalists and supranationalists, who

respectively abhorred and welcomed the creation of a centralized body with its

own sovereign powers, was won by the latter with the help of the CIA and

trans-Atlanticist elite organizations such as the Bilderberg Group.[17] After

the coming into existence of a single market in 1957, the European Union

gradually began to take shape and step by step has become more and more like a

“United States of Europe,” culminating in what is often regarded as the center piece

of European integration: the creation of a European Central Bank and the euro

as a common currency. As we have seen above, Africa under the leadership of

Gaddafi was moving in a similar direction with the emergence of supranational

organizations like the OAU, CEN-SAD and the AU. Furthermore, the continent was

gradually moving towards monetary integration as well.

The Abuja Treaty of 1991 established the African

Economic Community and outlined six stages for achieving a single monetary zone

for Africa by 2028. The final stage involved the creation of an African Central

Bank, an African Economic and Monetary Union and an African common currency.

The 1999 Sirte Declaration, spearheaded by Gaddafi, vowed to speed up this

process.[18] In addition, plans were underway to create an African

Monetary Fund that would only be open for African nations and would thus be

able to directly challenge neo-colonial institutions like the IMF and World

Bank.[19] Most

importantly, however, since his reorientation to Africa, Gaddafi repeatedly

urged for the establishment of a single African currency, lastly in February

2009 when he was elected chairman of the AU.[20]

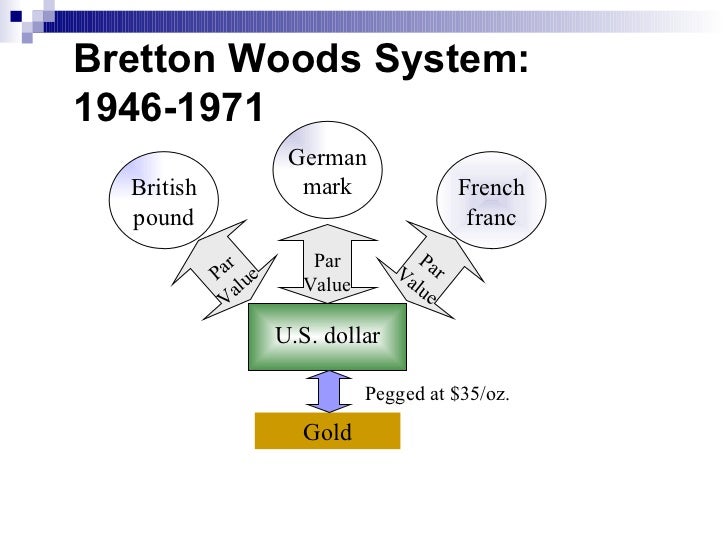

To fully understand the significance of Gaddafi’s

monetary endeavor, some background is needed. Under the Bretton Woods system, negotiated in the final

days of the Second World War, the US dollar became the backbone of the world

monetary system, convertible to gold at the fixed price of $35 per ounce with

all other currencies pegged to it. As the dollar grew weaker in the ensuing

decades, many nations including Germany and France started to demand gold for

their dollars, however, causing the US’s gold reserves to plunge. President

Nixon then abandoned the Bretton Woods system, and after the Western oiligarchs had

engineered the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, the petrodollar came into existence as a

replacement of the US gold standard. In this new system, Saudi Arabia,

then the largest OPEC oil exporter, pledged to price all of its future oil

sales in dollars and recycle its increased revenues through Atlanticist banking

institutions. Most petroleum-exporting nations followed suit and started to

trade their oil for dollars as well, thereby maintaining the dollar as the

world reserve currency, but

this time backed up by oil instead of gold.[21]

In 2000, Iraq,

which holds the world’s second largest oil reserves after Saudi Arabia, made

the political decision to dump the petrodollar and consequently started to

export almost all of its oil in euro’s.[22] Invasion and regime change quickly

followed. In January 2017, Iran also announced that it would stop using the

dollar as its currency of choice for its exports, the main commodity of

which is oil.[23]

As is blatantly obvious,

plans of toppling the Iranian government are well underway. Gaddafi not only wanted to ditch

the dollar for another currency as well, he wanted to create a new one, using

Libya’s own 144 tons of gold, a relatively large amount regarding its fairly

small population. Contrary to the dollar, which is for the most part made

out of thin air by private banking cartels,[24] the gold dinar would be steady and reliable as it would

be made from gold, a precious metal of which Africa has plenty in reserves.

Moreover, if in a future situation oil-rich African and Middle Eastern countries

would jump on the bandwagon and accept only gold in exchange for their oil as

well as other resources, the petrodollar would be replaced by a petro-gold

system.[25] The global

economy, then, would be built on the backbone of two commodities of which rich

Western countries possess less than the Global South. This would enable

the latter to throw off the neo-colonial chains of structural enslavement and

poverty and would in all likelihood cause the current global power structure to

collapse.

It is obvious that the “banksters” who currently control the global money

supply through their shares in central banks could not afford to let this

unfold. Three events, all happening in

the first two months of the conflict, signal the banksters’ role in the war.

First, the Obama administration froze $30 billion dollar in Libyan government

assets on 28 February. According to then Under Secretary for Terrorism and

Financial Intelligence David Cohen, this $30 billion dollar comprised the total

of the assets of the Libyan government, the Libyan Investment Authority and its

100% state-owned Central Bank.[26] Interestingly, part of this money was

reportedly earmarked for the Libyan contribution to the creation of the African

Investment Bank, the African Monetary Fund and the African Central Bank.[27] Second, by the end of March, the

rebels in Benghazi had created their own central bank while it was still all

but clear if they would succeed in toppling Gaddafi. This left even

mainstream analysts puzzled. “I have never before heard of a central bank being

created in just a matter of weeks out of a popular uprising,” noted Robert

Wenzel in Economic Policy Journal, “this suggests we have a bit

more than a rag tag bunch of rebels running around and that there are some

pretty sophisticated influences.”[28] Finally, a leaked email from early April

between Secretary of State

Hillary Clinton and her confidential adviser, Sid Blumenthal, confirms

the remaining threat of Gaddafi’s plan despite the freezing of Libyan assets.

In the email, titled “Re: France’s client & Qaddafi’s gold,” Blumenthal

states that

“Qaddafi’s government holds 143 tons of gold, and a

similar amount in silver. During late March, 2011, these stocks were moved to

SABHA (south west in the directs of the Libyan border with Niger and Chad);

taken from the vaults of the Libyan Central Bank in Tripoli. This gold was

accumulated prior to the current rebellion and was intended to be used to

establish a pan-African currency based on the Libyan golden Dinar. This plan

was designed to provide the Francophone African countries with an alternative

to the French franc (CFA).”[29]

The French aspect was of course

only the tip of the iceberg.

According to prof. Maximilian

Forte, NATO’s war on Libya sought to “disrupt an emerging pattern of

independence and a network of collaboration within Africa that would facilitate

increased African self-reliance.”[30] Gaddafi stood at the forefront of these

developments since the turn of the millennium, and his plan to create a

gold-backed African currency might have been a final catalyst to rendering

these developments irreversible. With the fiercest advocate of pan-Africanism

out of the way, it remains to be seen if internal divisions will be overcome or

not, however. As of June 2015, the African Union renewed talks on the

implementation of a pan-continental currency and an African Monetary Fund,[31]

but it is still unclear whether foreign “help” is going to be kept out and

whether newly formed pan-African institutions will be used to demand fair

profits for Africa’s abundant natural resources like Gaddafi envisioned.

Contemplating

another direction

I would like to finish with a

normative remark, because we threaten to fall into a false dilemma here.

Globalism as we know it today was set in motion in the West. Some 500 years

ago, Europe rapidly expanded overseas and soon colonized the whole world. It

then went on to plunder the Global South for several centuries by exploiting

its natural resources as well as its human labor through slavery, thereby

appropriating a huge advance in internal development. After decolonization,

however, structures that maintain global inequality remained in place through

centralized regimes; politically through the UN and NATO but also through more

obscure institutions like the Trilateral Commission and the Council on Foreign

Relations, and economically through the dollar as the world reserve currency as

well as the IMF and World Bank. These centralized regimes not only suppress the

Global South, however, they limit everyone’s freedom, move sovereignty even

further away from the individual and in essence, enslave humanity. Isn’t an

alternative centralization of power, i.e. a “United States of Africa” with a

single government and monopolized currency, then, not an imitation of the same

systems of repression that the Europeans and Americans imposed on Africa? If

successful, would it not impose an equally tyrannical system but with a different

face? As Frantz Fanon, a Martinique-born Caribbean revolutionary who, like

Gaddafi, was concerned with constructive African independence, wrote in 1961 in

the conclusion of his most famous work, Les damnés de la terre (The

wretched of the earth):

“Comrades, the European game is definitely over. We

must find something else. We can do everything today, provided that we won’t

imitate Europe, provided that we won’t be obsessed with overtaking Europe.

[...] Let us decide not to imitate Europe and let us mobilize our muscles and

brains in another direction. [...] Two centuries ago a former European colony

decided to overtake Europe. She succeeded so well in this that the United

States of America has become a monster, in which the defects, the diseases and the

inhumanity of Europe, have reached despicable dimensions. Comrades, don’t we

have something else to do than to work on the creation of a third Europe?”[32]

Notes

[1] Al-Gaddafi,

Muammar, address at UN General Assembly, New York, 23.09.2009.

[2] Dirk

Vandewalle, A history of modern Libya, 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2012).

[3] Vandewalle, A

history of Modern Libya, 150.

[4] Vandewalle, A

history of Modern Libya, 205.

[5] Muammar Gaddafi,

as cited in Hussein Solomon and Gerrie Swart, “Libya’s foreign policy in

flux,” African Affairs 104, no. 416 (2005), 479.

[6] Muammar Gaddafi,

as cited in Vandewalle, A history of Modern Libya, 196.

[7] Jason Hickel, “Aid

in reverse: how poor countries develop rich countries,” Guardian,

14.01.2017, http://theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/jan/14/aid-in-reverse-how-poor-countries-develop-rich-countries.

[8] “Inequality video

fact sheet,” The Rules, consulted on 20.05.2017, http://therules.org/inequality-video-fact-sheet/;

UN Development Programme, Human development report (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1999), 38, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/260/hdr_1999_en_nostats.pdf.

[9] Muammar Gaddafi,

speech at African Union Summit, 4-6.07.2005, as cited in Maximilian

Forte, Slouching towards Sirte: NATO’s war on Libya and Africa (Montreal:

Baraka Books, 2012), 150.

[10] Stephen

Okhonmina, “The African Union: pan-Africanist aspirations and the challenge of

African unity,” Journal of Pan African Studies 3, no. 4

(2009), 88-96.

[11] Forte, Slouching

towards Sirte, 137.

[12] Solomon and

Swart, “Libya’s foreign policy in flux,” 471-8; Forte, Slouching

towards Sirte, 156-66 and 171-2.

[13] Dan Glazebrook, “The

imperial agenda of the US’s ‘Africa Command’ marches on,” Guardian,

14.06.2012, http://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jun/14/africom-imperial-agenda-marches-on.

[14] Nick Turse, “The

war you’re never heard of,” Vice News, 18.05.2017, http://news.vice.com/story/the-u-s-is-waging-a-massive-shadow-war-in-africa-exclusive-documents-reveal?utm_content=buffercd547&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer.

[15] Solomon and

Swart, “Libya’s foreign policy in flux,” 478-82.

[16] African

Union, Fourth extraordinary session of the Assembly of Heads of State

and Government (Sirte, 8-9.09.1999), http://www.au2002.gov.za/docs/key_oau/sirte.pdf.

[17] Bas Spliet, “Soft

Power Centralization: the CIA, Bilderberg & the first steps towards

European integration,” Newsbud, 30.03.2017, http://newsbud.com/2017/03/30/soft-power-centralization-the-cia-bilderberg-the-first-steps-towards-european-integration/.

[18] Paul Masson and

Heather Milkiewicz, Africa’s economic morass - will a common currency

help? (Brookings institute: Policy brief #121, July 2003), 2, http://web.archive.org/web/20071009135255/http://www.brookings.edu/comm/policybriefs/pb121.pdf.

[19] Jean-Paul

Pougala, “Why the West wants the fall of Gaddafi,” Dissident Voice,

21.04.2011, http://dissidentvoice.org/2011/04/why-is-gaddafi-being-demonized/.

[20] Lydia Polgreen,

“Qaddafi, as new African Union head, will seek single state,” New York

Times, 02.02.2009, http://nytimes.com/2009/02/03/world/africa/03africa.html.

[21] James Corbett,

“How Big Oil engineered the Petrodollar,” International Forecaster,

05.01.2016, http://theinternationalforecaster.com/topic/international_forecaster_weekly/How_Big_Oil_Engineered_the_Petrodollar;

William F. Enghdahl, Myths, lies and oil wars (Wiesbaden:

edition.engdahl, 2012), 51-70; Pye Ian, “Oil on gold: the demise of the ponzi

petrodollar via a sustainable multi-commodity eastern alternative,” Newsbud,

11.05.2017, http://newsbud.com/2017/05/11/newsbud-exclusive-oil-on-gold-the-demise-of-the-ponzi-petrodollar-via-a-sustainable-multi-commodity-eastern-alternative/.

[22] Faisal Islam,

“Iraq nets handsome profit by dumping dollar for euro,” Guardian,

16.02.2003, http://theguardian.com/business/2003/feb/16/iraq.theeuro.

[23] Tyler Durden,

“Iran just officially ditched the dollar,” Zero Hedge,

02.02.2017, http://zerohedge.com/news/2017-02-02/iran-just-officially-ditched-dollar.

[24] Joe Wiesenthal,

“Everybody should read this explanation of where money really comes from,” Business

Insider, 27.04.2014, http://businessinsider.com/where-does-money-come-from-2014-4?IR=T.

[25] Anthony Wile,

“Gaddafi planned gold dinar, now under attack,” Daily Bell,

05.05.2011, http://thedailybell.com/editorials/anthony-wile-gaddafi-planned-gold-dinar-now-under-attack/;

Ellen Brown, “Why Qaddafi had to go: African, oil and the challenge to

monetary imperialism,” The Ecologist, 14.03.2016, http://theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2987399/why_qaddafi_had_to_go_african_gold_oil_and_the_challenge_to_monetary_imperialism.html;

William F. Engdahl, “Hillary emails, gold dinars and Arab springs,” New

Eastern Outlook, 17.03.2016, http://journal-neo.org/2016/03/17/hillary-emails-gold-dinars-and-arab-springs/.

[26] Jessica Hopper,

“U.S. freezes $30 billion in Libyan assets; Gadhafi called ‘delusional’,” ABC

News, 28.02.2011, http://abcnews.go.com/International/us-calls-gadhafi-delusional-freezes-30-billion-libyan/story?id=13017992.

[27] Pougala, “Why the

West wants the fall of Gaddafi.”

[28] Robert Wenzel,

“Libyan rebels form central bank,” Economic Policy Journal,

28.03.2011, http://economicpolicyjournal.com/2011/03/libyan-rebels-form-central-bank.html.

[29] Wikileaks, H:

France’s client & Q’s gold. Sid (Hillary Clinton Email Archive,

01.04.2011), http://wikileaks.org/clinton-emails/emailid/6528.

[30] Forte, Slouching

towards Sirte, 137.

[31] “African Union

renews talks on common currency, African monetary fund,” BRICS Post,

12.06.2015, http://thebricspost.com/african-union-renews-talks-on-common-currency-african-monetary-fund/#.WSK1LevyjIV.

[32] Original quote in

French; translated by the author to English. Frantz Fanon, Les damnés

de la terre (1961; reprint, Montréal: Université de Montréal, 2002),

300-1, http://fichier-pdf.fr/2011/12/16/damnes-de-la-terre/damnes-de-la-terre.pdf.

No comments:

Post a Comment