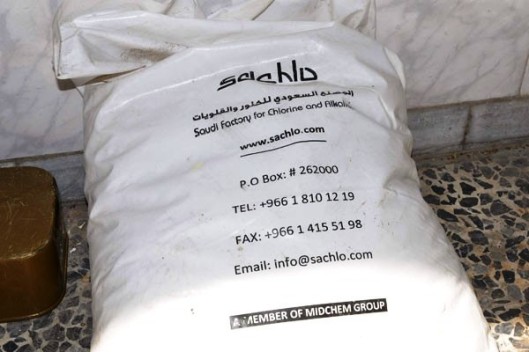

Above, chemical weapon ingredients from Saudi Arabia, a key nation fighting against Assad in Syria.

On Tuesday, the New York Times assigned two of its most committed anti-Syrian-government propagandists to cover the Syrian poison-gas story, Michael B. Gordon and Anne Barnard.

Gordon has been at the front

lines of the neocon “regime change” strategies for years. He co-authored the

Times’ infamous aluminum tube

story of Sept. 8, 2002, which relied on U.S. government sources

and Iraqi defectors to frighten Americans with images of “mushroom clouds” if

they didn’t support President George W. Bush’s upcoming invasion of Iraq. The

timing played perfectly into the administration’s advertising “rollout” for the

Iraq War.

Of course, the story turned out

to be false and to have unfairly downplayed skeptics of the claim that the

aluminum tubes were for nuclear centrifuges, when the aluminum tubes actually

were meant for artillery. But the article provided a great impetus toward the

Iraq War, which ended up killing nearly 4,500 U.S. soldiers and hundreds of

thousands of Iraqis.

Gordon’s co-author, Judith

Miller, became the only U.S. journalist known to have lost a job over the reckless

and shoddy reporting that contributed to the Iraq disaster. For his part,

Gordon continued serving as a respected Pentagon correspondent.

Gordon’s name also showed up in a

supporting role on the "Toilet Paper's" botched “vector

analysis,” which supposedly proved that the Syrian military was

responsible for the Aug. 21, 2013 sarin-gas attack. The “vector analysis” story

of Sept. 17, 2013, traced the flight paths of two rockets, recovered in

suburbs of Damascus back to a Syrian military base 9.5 kilometers away.

The article became the

“slam-dunk” evidence that the Syrian government was lying when it denied

launching the sarin attack. However, like the aluminum tube story, the Times’

”vector analysis” ignored contrary evidence, such as the unreliability of one

azimuth from a rocket that landed in Moadamiya because it had struck a building

in its descent. That rocket also was found to contain no sarin, so it’s

inclusion in the vectoring of two sarin-laden rockets made no sense.

But the Times’ story ultimately

fell apart when rocket scientists analyzed the one sarin-laden rocket that had

landed in the Zamalka area and determined that it had a maximum range of about

two kilometers, meaning that it could not have originated from the Syrian

military base. C.J. Chivers, one of the co-authors of the article, waited

until Dec. 28, 2013, to publish a

halfhearted semi-retraction. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “NYT Backs Off

Its Syria-Sarin Analysis.”]

Gordon was a co-author of another

bogus "Toilet Paper" front-page story on April 21, 2014, when the State Department and

the Ukrainian government fed the Times two photographs that supposedly proved

that a group of Russian soldiers – first photographed in Russia – had entered

Ukraine, where they were photographed again.

However, two days later, Gordon

was forced to pen a retraction because it turned out that both photos had been

shot inside Ukraine, destroying the story’s premise. [See Consortiumnews.com’s

“NYT Retracts

Russian-Photo Scoop.”]

Gordon perhaps personifies better

than anyone how mainstream journalism works. If you publish false stories that

fit with the Establishment’s narratives, your job is safe even if the stories

blow up in your face. However, if you go against the grain – and if someone

important raises a question about your story – you can easily find yourself out

on the street even if your story is correct.

Anne Barnard, Gordon’s co-author

on Tuesday’s Syrian poison-gas story, has consistently reported on the Syrian

conflict as if she were a press agent for the rebels, playing up their

anti-government claims even when there’s no evidence.

For instance, on June 2, 2015,

Barnard, who is based in Beirut, Lebanon, authored a front-page story that

pushed the rebels’ propaganda theme that the Syrian government was somehow in cahoots

with the Islamic State though even the U.S. State Department

acknowledged that it had no confirmation of the rebels’ claims.

When Gordon and Barnard teamed up

to report on the

latest Syrian tragedy, they again showed no skepticism about early

U.S. government and Syrian rebel claims that the Syrian military was

responsible for intentionally deploying poison gas.

Perhaps for the first time, The

New York Times cited President Trump as a reliable source because he and his

press secretary were saying what the Times wanted to hear – that Assad must be

guilty.

Gordon and Barnard also cited the controversial

White Helmets, the rebels’ Soros-financed civil defense group that

has worked in close proximity with Al Qaeda’s Nusra Front and has come under

suspicion of staging heroic “rescues” but is nevertheless treated as a fount of

truth-telling by the mainstream U.S. news media.

In early online versions of the

Times’ story, a reaction from the Syrian military was buried deep in the

article around the 27th paragraph, noting: “The government denies that it

has used chemical weapons, arguing that insurgents and Islamic State fighters

use toxins to frame the government or that the attacks are staged.”

The following paragraph mentioned

the possibility that a Syrian bombing raid had struck a rebel warehouse where

poison-gas was stored, thus releasing it unintentionally.

But the placement of the response

was a clear message that the Times disbelieved whatever the Assad government

said. At least in the version of the story that appeared in the morning

newspaper, a government statement was moved up to the sixth paragraph although

still surrounded by comments meant to signal the Times’ acceptance of the rebel

version.

After noting the Assad

government’s denial, Gordon and Barnard added, “But only the Syrian military

had the ability and the motive to carry out an aerial attack like the one that

struck the rebel-held town of Khan Sheikhoun.”

But they again ignored the

alternative possibilities. One was that a bombing raid ruptured containers for

chemicals that the rebels were planning to use in some future attack, and the

other was that Al Qaeda’s jihadists staged the incident to elicit precisely the

international outrage directed at Assad as has occurred.

Gordon and Barnard also could be

wrong about Assad being the only one with a motive to deploy poison gas. Since

Assad’s forces have gained a decisive upper-hand over the rebels, why would he

risk stirring up international outrage at this juncture? On the other hand, the

desperate rebels might view the horrific scenes from the chemical-weapons

deployment as a last-minute game-changer.

None of this means that Assad’s

forces are innocent, but a serious investigation ascertains the facts and then

reaches a conclusion, not the other way around.

However, to suggest these other

possibilities will, I suppose, draw the usual accusations about “Assad

apologist,” but refusing to prejudge an investigation is what journalism is

supposed to be about.

The Times, however, apparently

has no concern anymore for letting the facts be assembled and then letting them

speak for themselves. The Times weighed in on Wednesday with an editorial

entitled “A New Level

of Depravity From Mr. Assad.”

Another problem with the behavior

of the Times and the lame stream media is that by jumping to a conclusion they

pressure other important people to join in the condemnations and that, in turn,

can prejudice the investigation while also generating a dangerous momentum

toward war.

Once the political leadership

pronounces judgment, it becomes career-threatening for lower-level officials to

disagree with those conclusions. We’ve seen that already with how United

Nations investigators accepted rebel claims about the Syrian government’s use

of chlorine gas, a set of accusations that the Times and other media now report

simply as flat-fact.

Yet, the claims about the Syrian

military mixing in canisters of chlorine in supposed “barrel bombs” make little

sense because chlorine deployed in that fashion is ineffective as a lethal

weapon but it has become an important element of the rebels’ propaganda

campaign.

U.N. investigators, who were

under intense pressure from the United States and Western nations to give them

something to use against Assad, did support rebel claims about the government

using chlorine in a couple of cases, but the investigators also received

testimony from residents in one area who described the staging of a chlorine

attack for propaganda purposes.

One might have thought that the

evidence of one staged attack would have increased skepticism about the other

incidents, but the U.N. investigators apparently understood what was good for

their careers, so they endorsed a couple of other alleged cases despite their

inability to conduct a field investigation. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “UN Team Heard

Claims of Staged Chemical Attacks.”]

Now, that dubious U.N. report is

being leveraged into this new incident, one opportunistic finding used to

justify another. But the pressing question now is: Have the American people

come to understand enough about “psychological

operations” and “strategic

communications” that they will finally show the skepticism that no

longer exists in the major U.S. news media?

No comments:

Post a Comment