Missouri authorities have quietly

adopted an emergency plan in case the smoldering embers ever reach the waste, a

potentially "catastrophic event" that could release radioactive

fallout in a plume of smoke over a densely populated area of suburban St.

Louis.

Below is Daboo7's video on the Westlake landfill.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QiEA6rzpcIE

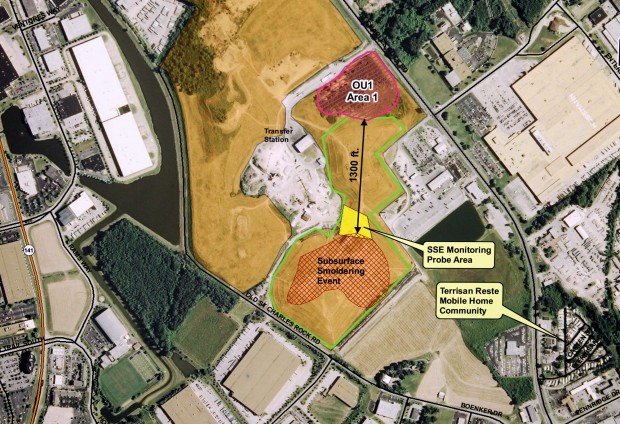

There's a fire burning in Bridgeton, Missouri. It's invisible to area residents, buried deep beneath the ground in a North St. Louis County Bridgeton landfill, pictured below. But the smoldering waste is an unavoidable presence in town, giving off a putrid odor that clouds the air miles away – an overwhelming stench described by one area woman as "rotten eggs mixed with skunk and fertilizer." "It smells like dead bodies," observes another local.

The landfill's owner, Republic Services, sent glossy fliers to residents within stink radius claiming the noxious odor posed no safety risk. But official reports say otherwise. Temperature probes reveal the fire has already surpassed normal heat levels. Reports from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) indicate dangerously high levels of benzene and hydrogen sulfide in the air. Missouri's Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) – which has jurisdiction over Bridgeton Landfill – quietly posted an Internet notice cautioning citizens with chronic respiratory diseases to limit time outdoors. A month after Republic distributed its flier, the state attorney general sued the company on eight counts of environmental violations, including pollution and public nuisance. Republic sent another round of fliers offering to move local families to hotels during a period of increased odor related to remediation efforts.

The landfill fire is burning close to at least 8,700 tons of nuclear weapons wastes.

West Lake Landfill is an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund site that's home to some of the oldest radioactive wastes in the world. A six-foot chain-link fence surrounds the perimeter, plastered with bright yellow hazard signs that warn of the dangers within. On one corner stands a rusty gas pump. About 1,200 feet south of the radioactive EPA site, the fire at Bridgeton Landfill spreads out like hot barbeque coals. No one knows for sure what happens when an underground inferno meets a pool of atomic waste, but residents aren't eager to find out.

Peter Anderson – an economist who has studied landfills for over 20 years, raised the worst-case scenario of a "dirty bomb," meaning a non-detonated, mass release of floating radioactive particles in metro St. Louis. A dirty bomb is not nuclear fission, it's not an atomic bomb, it's not a weapon of mass destruction But the dispersal of that radioactive material in air that could reach, depending upon weather conditions, as far as 10 miles from the site could make it impossible to have economic activity continue and it would contaminate all the soil for up to 10 miles.

Republic Services says, "Mr. Anderson made his statement without any proof or evidence, and he ignored the fact that ongoing evaluation by MDNR, EPA and local authorities have confirmed that the increased heat at the Bridgeton Landfill has not impacted West Lake and does not pose a threat to the materials at West Lake."

Republic Services also denies that it is dealing with a "fire" – the company prefers the euphemism "subsurface smoldering event." Under orders from the state, Republic is drilling holes to contain this "smoldering event." Republic estimates it's already spent over $20 million – about 0.25 percent of its 2012 revenues – on such mitigation efforts, "not because we have to, but because it is the right thing to do."

Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster sued Republic Services, and outlined odor pollution and public health violations at Bridgeton Landfill, he described the risk of the fire contacting the nearby radioactive waste as a mere "remote hypothetical." But many residents are far from reassured.

The story of West Lake's radioactive waste goes back to April 1942, when a St. Louis company called Mallinckrodt Chemical Works began purifying tens of thousands of tons of uranium for the University of Chicago as part of the Manhattan Project. Mallinckrodt's workers did not receive adequate safety protections and had little knowledge of what they were dealing with – oversights that would lead to disproportionately high cancer death rates among workers, as documented in books, dissertations and journalistic accounts, including a groundbreaking seven-part series from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1989. Over the next 25 years, the company's uranium processing also created huge amounts of radioactive waste, much of which was secretly dumped at sites throughout the St. Louis metropolitan area, including West Lake.

Today, West Lake's radioactive waste – all 143,000 cubic yards of it – sits on the outskirts of a former quarry with practically none of the standard safety features found in most municipal landfills. No clay liner blocks toxic leachate – or "garbage juice" – from seeping into area groundwater. No cap keeps toxic gas from dispersing into the air. This unprotected waste sits on a floodplain 1.5 miles away from the Missouri River. Eight miles downstream is a drinking water reservoir that serves 300,000 St. Louisans.

Worst of all: The materials dumped in this populous metropolitan area will continue to pose a hazard for hundreds of thousands of years.

Dan Gravatt is the EPA manager tasked with handling West Lake .

In 2008, the EPA decided to cap the radiotoxic material dumped at West Lake and leave it there. Capping the site meant piling five feet of dirt and rocks on top and implementing long-term monitoring for contamination. Facing widespread public pressure, including a letter from St. Louis mayor Francis Slay, the EPA postponed its decision pending further studies.

Kay Drey is an 80-year-old civil rights and anti-nuclear activist who's been advocating for the removal of wastes from the St. Louis area for more than three decades. Drey said, "I was very disappointed, The evidence is clear. This is radioactively hot stuff and it shouldn't be in the floodplain by the Missouri river. And if they can't admit to that – well, it's incomprehensible."

Back at his office, Gravatt insists that West Lake's radioactive wastes only pose health risks for people who come in direct contact with the site, adding that the nuclear dump "doesn't pose any current exposure pathways to area residents as it stands now."

But Robert Criss, a geochemist at Washington University in St. Louis who has studied the issue closely, says the EPA is grossly underplaying a host of risks surrounding West Lake – flooding, earthquakes, liquefaction, groundwater leaching – that could pave the way for a public health crisis. That's not to mention the recent development of an underground fire nearby. Says Criss, "There is no geological site I can think of that is more absurd to place such waste."

Digging through old Nuclear Regulatory Commission studies, he recently stumbled upon what he describes as an error with major implications. For the last three decades, various government documents have referred to the waste at the landfill as "leached barium sulfate," a nearly insoluble compound generated from uranium processing. But Criss says that the NRC's own data shows the material dumped at West Lake contains far too little barium and sulfate to compose barium sulfate – by factors of 100 and 1000, respectively. "If I had this long to study something, I would be pretty embarrassed if this is what I came up with," says Criss. "It is inconceivable for these people to promote remedies when they don't even know what they're dealing with."

the EPA disputes Criss' findings, but declined to offer further explanation, instead deferring to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Upon request for a chemical analysis proving the waste is barium sulfate West Lake remains under federal jurisdiction, only an act of Congress could transfer the site to the Army Corps.

The underground fire was news to Ramona Herbert, who moved to Spanish Village with her family last November. She and her husband, Joshua, came here from St. Louis' inner city, hoping for a safer place to raise their kids. When the Herberts signed a five-year lease for their new home, no one disclosed to them that hot nuclear dumps sit a mile north from their children's bedrooms. No one told the Herberts that an ongoing landfill fire burns just down the street from their local Bob Evans restaurant. "My landlord said to me that we have a little sewage problem," she recalls. "So I'm thinking the sewage system isn't working right." But the stench only got worse, and she started having trouble sleeping. Parents stopped letting 14-year-old Mateo Herbert's friends shoot hoops in his neighborhood, because something in the air was making their kids' eyes water. And Joshua Herbert, who boasted a nearly spotless medical history, started suffering terrible headaches. Like hundreds of other concerned citizens in North St. Louis, she wants answers. "When were we going to be warned?" Herbert wonders, standing at the door of her new home. "When is it too late?"

Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster sued Republic Services in 2013,

alleging negligent management and violation of state environmental laws. The

case is scheduled to go to trial in March 2016.

Last

month, Koster said he was troubled by new reports about the site. One found radiological

contamination in trees outside the landfill's perimeter. Another showed

evidence that the fire has moved past two rows of interceptor wells and closer

to the nuclear waste.

Koster

said the reports were evidence that Republic Services "does not have this

site under control." Republic Services responded by accusing the state of

intentionally exacerbating "public angst and confusion."

No comments:

Post a Comment