Revelation 6:12 And the sixth angel poured out his vial upon

the great river Euphrates; and the water thereof was dried up, that the way of

the kings of the east might be prepared.

A large portion of the Middle East lost freshwater reserves rapidly during the past decade. Data revealed an arid region of Tigris-Euphrates Basin, which grows even drier due to human consumption of water for drinking and agriculture. The research team observed the Tigris and Euphrates river basins - including parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, and found that 144 cubic kilometers (117 million acre feet) of fresh water was lost from 2003 to 2009 - the roughly equivalent to the volume of the Dead Sea. About 60% of the loss was attributed to the pumping of groundwater from underground reservoirs. When a drought shrinks the available surface water supply, irrigators and others turn to groundwater.

The team led by Jay Famiglietti and Kate Voss of the University of California–Irvine (UCI) and Georgetown University with other researchers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, used data acquired by twin gravity-measuring satellites of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE).

According to Jay Famiglietti, GRACE data show an alarming rate of decrease in total water storage in the Tigris and Euphrates river basins, which currently have the second fastest rate of groundwater storage loss on Earth, after India. The rate was especially striking after the 2007 drought. Meanwhile, demand for freshwater continues to rise, and the region does not coordinate its water management because of different interpretations of international laws.

GRACE data show a

seasonal fluctuation of total water storage, and also an overall downward

trend, suggesting that groundwater is being pumped and used faster than natural

processes can replenish it. Within any given region on Earth, rising or

falling water reserves alter the planet’s mass, influencing the gravity field

of the area. GRACE satellites tells us how water storage changes over time by periodically

measuring gravity in each region.

The researchers calculated that about one-fifth of the water losses in their Tigris-Euphrates study region came from snow pack shrinking and soil drying up, partly in response to a 2007 drought. Another fifth of the losses is caused by loss of surface water from lakes and reservoirs. The majority of the loss—approximately 73 million acre feet (90 cubic kilometers)—was due to reductions in groundwater. According to Jay Famiglietti, principal investigator of the study, that's enough water to meet the needs of tens of millions to more than a hundred million people in the region each year, depending on regional water-use standards and availability.

The researchers calculated that about one-fifth of the water losses in their Tigris-Euphrates study region came from snow pack shrinking and soil drying up, partly in response to a 2007 drought. Another fifth of the losses is caused by loss of surface water from lakes and reservoirs. The majority of the loss—approximately 73 million acre feet (90 cubic kilometers)—was due to reductions in groundwater. According to Jay Famiglietti, principal investigator of the study, that's enough water to meet the needs of tens of millions to more than a hundred million people in the region each year, depending on regional water-use standards and availability.

The 754,000-square-kilometer (291,000-square-miles) Tigris and Euphrates basin jumped out as a hotspot when UC Irvine researchers looked at the global water ups and down. Within the seven-year period of GRACE data, researchers calculated that water storage in the region shrunk by an average of 20 cubic km (16 million acre feet) a year. This rate of water loss is among the largest liquid freshwater losses on the continents. Meanwhile, the region’s demand for fresh water is rising.

“They just do not have that much water to begin with, and they’re

in a part of the world that will be experiencing less rainfall with climate

change. Those dry areas are getting dryer,” Famiglietti said. “They and

everyone else in the world’s arid regions need to manage their available water

resources as best they can.”

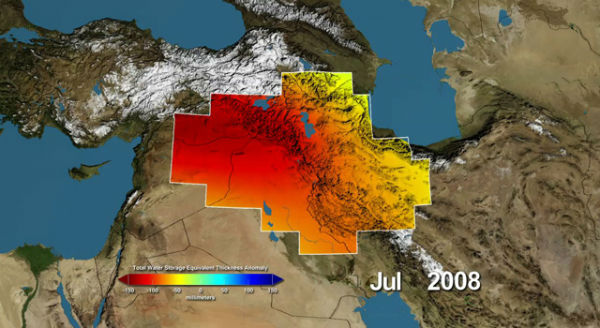

Notice the above image: Variations in total water storage from normal, in millimeters, in the Tigris and Euphrates river basins, as measured by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, from January 2003 through December 2009. Reds represent drier conditions, while blues represent wetter conditions. The majority of the water lost was due to reductions in groundwater caused by human activities. By periodically measuring gravity regionally, GRACE tells scientists how much water storage changes over time.

I wrote the article below in August 2009.

Earthly Signs - Euphrates & Tigris Drying Up

|

| An Iraqi stuck in the Euphrates mud |

|

| This photo vividly shows how the banks of the Tigris are shrinking |

|

| An Iraqi gathers salt from the drying river near the Persian Gulf |

This week I have been writing about Heavenly signs now it appears a key earthly sign is taking place in Iraq. The Euphrates and Tigris rivers are drying up. When I was with the U.S. Army in Iraq I was amazed at Iraqi and Babylonian agricultural ingenuity. Iraq’s vast irrigation canals feeding off the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers are indeed an agricultural marvel and a unique and powerful blessing to Iraq.

While in Iraq I also learned that for thousands of years The Prince of Persia, one of Satan’s demons rules over Iraq/Babylon region. Satan and the Prince do not want to give up this vast area and the forces of darkness are fighting to the death against the Iraqi people, their U.S. allies and the Assyrian, Chaldean and other Christians in Iraq. I believe another factor that contributes to Iraq’s water problem is the fact that Christians are being persecuted and martyred in Iraq by violent Muslims. Think about the Biblical passages that follow.

The Euphrates River

The sixth angel voices his commands and four demons (fallen angels are loosed from the Euphrates River in Iraq. A total of 200 million troops come to the Middle East from the Orient. The Euphrates dries up so that the kings of the East can cross over to fight the Battle of Armageddon. Chapters 9 and 16 of the Book of Revelation mention the Euphrates as a focal point in the war.

In Isaiah Chapter 11 it is written: 10 In that day the Root of Jesse will stand as a banner for the peoples; the nations will rally to him, and his place of rest will be glorious. 11 In that day the Lord will reach out his hand a second time to reclaim the remnant that is left of his people from Assyria, from Lower Egypt, from Upper Egypt, [b] from Cush, [c] from Elam, from Babylonia, [d] from Hamath and from the islands of the sea. 12 He will raise a banner for the nations and gather the exiles of Israel; he will assemble the scattered people of Judah from the four quarters of the earth. 13 Ephraim's jealousy will vanish, and Judah's enemies [e] will be cut off; Ephraim will not be jealous of Judah, nor Judah hostile toward Ephraim. 14 They will swoop down on the slopes of Philistia to the west; together they will plunder the people to the east. They will lay hands on Edom and Moab, and the Ammonites will be subject to them. 15 The LORD will dry up the gulf of the Egyptian sea; with a scorching wind he will sweep his hand over the Euphrates River. [f] He will break it up into seven streams so that men can cross over in sandals. 16 There will be a highway for the remnant of his people that is left from Assyria, as there was for Israel when they came up from Egypt. Isaiah 11:10-16

Footnotes:

a. Isaiah 11:11 Hebrew from Pathros

b. Isaiah 11:11 That is, the upper Nile region

c. Isaiah 11:11 Hebrew Shinar

d. Isaiah 11:13 Or hostility

e. Isaiah 11:15 Hebrew the River

In Iraq's southern marshes, the reed gatherers, standing on land they once floated over, cry out to visitors in a passing boat.“Maaku mai!” they shout, holding up their rusty sickles. “There is no water!” The Euphrates is drying up. Strangled by the water policies of Iraq’s neighbors, Turkey and Syria; a two-year drought; and years of misuse by Iraq and its farmers, the river is significantly smaller than it was just a few years ago. Some officials worry that it could soon be half of what it is now. The shrinking of the Euphrates, a river so crucial to the birth of civilization that the Book of Revelation prophesied its drying up as a sign of the end times, has decimated farms along its banks, has left fishermen impoverished and has depleted riverside towns as farmers flee to the cities looking for work. The poor suffer more acutely, but all strata of society are feeling the effects: sheiks, diplomats and even members of Parliament who retreat to their farms after weeks in Baghdad. Along the river, rice and wheat fields have turned to baked dirt. Canals have dwindled to shallow streams, and fishing boats sit on dry land. Pumps meant to feed water treatment plants dangle pointlessly over brown puddles. “The old men say it’s the worst they remember,” said Sayid Diyia, 34, a fisherman in Hindiya, sitting in a riverside cafe full of his idle colleagues. “I’m depending on God’s blessings.”

The Euphrates River

The sixth angel voices his commands and four demons (fallen angels are loosed from the Euphrates River in Iraq. A total of 200 million troops come to the Middle East from the Orient. The Euphrates dries up so that the kings of the East can cross over to fight the Battle of Armageddon. Chapters 9 and 16 of the Book of Revelation mention the Euphrates as a focal point in the war.

In Isaiah Chapter 11 it is written: 10 In that day the Root of Jesse will stand as a banner for the peoples; the nations will rally to him, and his place of rest will be glorious. 11 In that day the Lord will reach out his hand a second time to reclaim the remnant that is left of his people from Assyria, from Lower Egypt, from Upper Egypt, [b] from Cush, [c] from Elam, from Babylonia, [d] from Hamath and from the islands of the sea. 12 He will raise a banner for the nations and gather the exiles of Israel; he will assemble the scattered people of Judah from the four quarters of the earth. 13 Ephraim's jealousy will vanish, and Judah's enemies [e] will be cut off; Ephraim will not be jealous of Judah, nor Judah hostile toward Ephraim. 14 They will swoop down on the slopes of Philistia to the west; together they will plunder the people to the east. They will lay hands on Edom and Moab, and the Ammonites will be subject to them. 15 The LORD will dry up the gulf of the Egyptian sea; with a scorching wind he will sweep his hand over the Euphrates River. [f] He will break it up into seven streams so that men can cross over in sandals. 16 There will be a highway for the remnant of his people that is left from Assyria, as there was for Israel when they came up from Egypt. Isaiah 11:10-16

Footnotes:

a. Isaiah 11:11 Hebrew from Pathros

b. Isaiah 11:11 That is, the upper Nile region

c. Isaiah 11:11 Hebrew Shinar

d. Isaiah 11:13 Or hostility

e. Isaiah 11:15 Hebrew the River

In Iraq's southern marshes, the reed gatherers, standing on land they once floated over, cry out to visitors in a passing boat.“Maaku mai!” they shout, holding up their rusty sickles. “There is no water!” The Euphrates is drying up. Strangled by the water policies of Iraq’s neighbors, Turkey and Syria; a two-year drought; and years of misuse by Iraq and its farmers, the river is significantly smaller than it was just a few years ago. Some officials worry that it could soon be half of what it is now. The shrinking of the Euphrates, a river so crucial to the birth of civilization that the Book of Revelation prophesied its drying up as a sign of the end times, has decimated farms along its banks, has left fishermen impoverished and has depleted riverside towns as farmers flee to the cities looking for work. The poor suffer more acutely, but all strata of society are feeling the effects: sheiks, diplomats and even members of Parliament who retreat to their farms after weeks in Baghdad. Along the river, rice and wheat fields have turned to baked dirt. Canals have dwindled to shallow streams, and fishing boats sit on dry land. Pumps meant to feed water treatment plants dangle pointlessly over brown puddles. “The old men say it’s the worst they remember,” said Sayid Diyia, 34, a fisherman in Hindiya, sitting in a riverside cafe full of his idle colleagues. “I’m depending on God’s blessings.”

The drought was widespread in Iraq in 2007. The area sown with wheat and barley in the rain-fed north is down roughly 95 percent from the usual, and the date palm and citrus orchards of the east are parched. For two years rainfall has been far below normal, leaving the reservoirs dry, and American officials predict that wheat and barley output will be a little over half of what it was two years ago.

It is a crisis that threatens the roots of Iraq’s identity, not only as the land between two rivers but as a nation that was once the largest exporter of dates in the world, that once supplied German beer with barley and that takes patriotic pride in its expensive Anbar rice. Now Iraq is importing more and more grain. Farmers along the Euphrates say, with anger and despair, that they may have to abandon Anbar rice for cheaper varieties.

Droughts are not rare in Iraq, though officials say they have been more frequent in recent years. But drought is only part of what is choking the Euphrates and its larger, healthier twin, the Tigris. The most frequently cited culprits are the Turkish and Syrian governments. Iraq has plenty of water, but it is a downstream country. There are at least seven dams on the Euphrates in Turkey and Syria and with no treaties or agreements, the Iraqi government is reduced to begging its neighbors for water.

At a conference in Baghdad — where participants drank bottled water from Saudi Arabia, (SA) a country with a fraction of Iraq’s fresh water — officials spoke of disaster. (When I was with the U.S. Army in Iraq we drank bottled water from SA.) “We have a real thirst in Iraq,” said Ali Baban, the minister of planning. “Our agriculture is going to die, our cities are going to wilt, and no state can keep quiet in such a situation.” Recently, the Water Ministry announced that Turkey had doubled the water flow into the Euphrates, salvaging the planting phase of the rice season in some areas.That move increased water flow to about 60 percent of its average, just enough to cover half of the irrigation requirements for the summer rice season. Though Turkey has agreed to keep this up and even increase it, there is no commitment binding the country to do so.With the Euphrates showing few signs of increasing health, bitterness over Iraq’s water threatens to be a source of tension for months or even years to come between Iraq and its neighbors.

A large part of the problem lies in Iraq’s own deplorable water management policies. Saddam built expensive palaces all over Iraq but when it came to public administrators of Iraq’s resources and wealth he was horrible. “There used to be water everywhere,” said Abduredha Joda, 40, sitting in his reed hut on a dry, rocky plot of land outside Karbala. Mr. Joda, who describes his dire circumstances with a tired smile, grew up near Basra but fled to Baghdad when Saddam Hussein drained the great marshes of southern Iraq in retaliation for the 1991 Shiite uprising. He came to Karbala in 2004 to fish and raise water buffaloes in the lush wetlands there that remind him of his home.“This year it’s just a desert,” he said. Along the river, there is no shortage of resentment at the Turks and Syrians, Americans, Kurds, Iranians and the Iraqi government, all of whom are blamed. Scarcity makes everyone an enemy.

The sectarian conflict even includes water. The Sunni areas upriver seem to have enough water, Mr. Joda observed, a comment heavy with implication.

Officials say nothing will improve if Iraq does not seriously address its own water policies and its history of flawed water management. Leaky canals and wasteful irrigation practices squander the water, and poor drainage leaves fields so salty from evaporated water that women and children dredge huge white mounds from sitting pools of runoff. On a scorching morning in Diwaniya, Bashia Mohammed, 60, was working in a drainage pool by the highway gathering salt, her family’s only source of income now that its rice farm has dried up. But the dead farm was not the real crisis. “There’s no water in the river that we drink from,” she said, referring to a channel that flows from the Euphrates. “It’s now totally dry, and it contains sewage water. They dig wells but sometimes the water just cuts out and we have to drink from the river. All my kids are sick because of the water.”

In the southeast, where the Euphrates nears the end of its 1,730-mile journey and mingles with the less salty waters of the Tigris before emptying into the Persian Gulf, the situation is grave. The marshes there that were intentionally re-flooded in 2003, rescuing the ancient culture of the marsh Arabs, are drying up again. Sheep graze on land in the middle of the river.The farmers, reed gatherers and buffalo herders keep working, but they say they cannot continue if the water stays like this. “Next winter will be the final chance,” said HashemHilead Shehi, a 73-year-old farmer who lives in a bone-dry village west of the marshes. “If we are not able to plant, then all of the families will leave.”

No comments:

Post a Comment